Introduction

Over the last decade, there has been an increase in interest in buying and selling of certain music industry assets, primarily publishing rights and master recordings. An acceleration of a long occurring industry trend sees more musicians and songwriters selling their intellectual property rights to large financial institutions, private equity firms, asset managers, and pension funds, as well as to more traditional buyers such as major record labels and music publishers. This is a tangible shift in an often unseen part of the music industry. The large price tags of the catalogs that have been sold, as well as the vast number of famous artists selling their rights to popular songs, has even sparked widespread media interest outside of the traditional music business press with more mainstream publications. Many people, in and outside of the music industry, have begun to wonder what the implications of this change may be for artists, songwriters, and the entire music industry.

Songwriting catalogs being viewed and traded as assets can be traced back more than a century to Tin Pan Alley, a cluster of blocks within Manhattan, New York, where many early music publishers were formed to distribute the work of songwriters. These early publishers signed artists and bought the rights to songwriters’ compositions with the goal of marketing, licensing, and promoting these songs to radio, jukeboxes, and whatever new forms of mass media exist, so they make a return on their investments. As the compositions that they owned grew in popularity and profitability, these publishers would sell these publishing assets to larger firms, and/or use the financial gains to purchase additional catalogs themselves. It did not take long before the ownership in performers’ released recordings, known as ‘master recordings’, also became financial investments. Early record labels would often purchase these master recordings with the hope that royalties or a future sale of those recordings would more than make up for their costs.

The status of musical compositions and other music related intellectual property, known as ‘IP’, as a financial asset transcends evolutions in technology and infrastructure. Over the last one hundred years, notable moments in this process of development include Michael Jackson’s purchase of The Beatles’ catalog in the mid-80s, David Bowie’s attempt at selling an asset-backed security attached to his music (i.e. Bowie Bonds) during the late ’90s CD peak, and the recent uptick in rights sold by artists from the likes of superstars Bob Dylan to various companies including major labels, asset managers, private equity companies, pension funds, and many other institutional investors. Artists and industry professionals recognized a renewed interest in the cultural and financial capital present in music rights ownership, and have uniquely leveraged this value to generate billions of dollars in catalog sales and purchases the last couple of decades. It is in this last development where we see a real divergence from the past in how this sector of the industry operated and what we aim to highlight in this report.

The evolution of music IP from art to financial asset has had many steps, but a recent development that has significantly altered this ever-changing space is the introduction of large private capital investment in music IP. The deep pockets of these investment firms and their ferocious appetites for purchases, have inflated the values of music IP on the open market, and have allowed songwriters and other music IP owners to set high price tags for the rights to their repertoire. With streaming and other traditional music revenue streams providing paltry payouts in the current streaming-centric music economy, financial strain has led more and more rights holders to sell some or all of their IP to these large investment firms. This was only accelerated in 2020 with the coronavirus pandemic shutting down live music, which for many musicians, especially ones with robust catalogs, was their primary method of making money. But what is it exactly that these investors are buying and what are the goals of these large-scale acquisitions?

This report will examine how various song and administration rights are being sold, and analyze the ways in which these rights can be exploited both regionally and internationally. The first section will analyze the history of American music publishing in the 20th century, where we will show how this sector saw a rise, then decline in perceived value, as recorded music began to replace sheet music as the industry’s primary commodity. This devaluing of music publishing saw it begin to act as a junior partner to many record labels, as the two parts of the industry became more intermingled and consolidated throughout the second half of the century. Next the paper will explain the various kinds of copyrights for musicians, in order to better and clearly understand what is being held at these astronomical numbers. The third section returns back to the history of music publishing, but now looking closely at the 21st century and in particular the sale of music catalogs by firms backed by large financial players. This is where country pension funds, asset managers, and private equity firms really start to make a name for themselves in the space. The fourth section will provide a brief history of music catalog purchases within France, with an eye towards identified emerging companies within Europe that are trying to buy up their own bundles of song rights. Then the paper will close with a final summary about what are the potential ramifications for these deals and alternatives to private industry exploitation of these catalogs. Then a proposal for civic intervention in the ownership of song rights, positing music as a talisman of both economic prosperity and cultural heritage. The injection of investment money and increased attention to song catalogs allows songwriters and master owners to cash-in in the short term; there are real questions about the long-term viability of music as a private asset class. What are the implications of the public and artistic value of music reduced only to the revenue it generates?

American Music Publishing in the 20th Century

In the late 19th and early 20th century, the music business was centered around publishing, in particular the buying and selling of sheet music. It was this format that helped create many of the early foundations for what would become the recorded music business. However, in the mid-1920s when sound recording technology emerged, it flipped the dynamics of the industry on its head. No longer were music fans buying sheet music to perform at home, but instead they were purchasing recordings. This new emphasis on recorded music placed much more power in the hands of the new up-and-coming record labels, rather than publishers. Still, early publishers were able to hold successful songwriters under exclusive contracts, which allowed them to build large and valuable catalogs of compositions and publishing rights.

The business transformed again in the 1960s, when artists themselves began to take notice of the value of their music catalogs, and established their own means of controlling and administering publishing rights. Perhaps the most famous of these artist-held publishing endeavors is Northern Songs Ltd, the company founded in 1963 by John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Brian Epstein and Dick James to publish the catalog written by Lennon and McCartney for The Beatles. Yet only a few years later in 1969, a majority stake in Northern Songs was sold to Britain’s Associated Television (ATV). Unfortunately for Lennon and McCartney, the artists who had built the company to control the rights to their works, this sale was completed without their knowledge or approval. Though the two songwriters continued to hold a minority share in their catalog, they had no controlling interest in the exploitation of the publishing rights, and effectively lost control of their catalog. This sale to ATV is indicative not only of the wider conglomeration of the publishing business, which continued throughout the 20th century, but also of the ways in which the financialization of music catalogs privileged the business stakeholders over the artists who had created the works being held.

The 1960s and 1970s saw the slow rolling up of smaller publishers across North America and Europe into a handful of major ones. At the time, a majority of those deals were coming from within the industry itself, with larger music publishing companies purchasing smaller ones. That started to shift in the early 1980s. Freddy Bienstock, a record industry veteran who built his name helping place Elvis Presley songs in films, was part of the wave of publisher consolidation. But in March 1983, Bienstock along with the Rodgers and Hammerstein estate, and the investment firm Wertheim & Co. purchased the Edward B. Marks catalog for $5 million.1Irv Litchman, ‘Oldline Publishing Firm E.B. Marks Music Sold’, Billboard, 1983-03-12, p74, online: www.worldradiohistory.com/Archive-All-Music/Billboard/80s/1983/BB-1983-03-12.pdf.That deal would foreshadow one of the biggest publishing purchases of the 1980s, when the same consortium of industry players paid $100 million for Chappell, then the world’s largest music publisher, from Polygram Records in 1984. 2Sandra Salmans, ‘A Song Plugger’s Biggest Play: His Return As Boss’, The New York Times, 1985-06-04, online: www.nytimes.com/1985/06/04/business/new-yorkers-co-a-song-plugger-s-biggest-play-his-return-as-boss.html.This was one of the first large occurrences of a non-music industry financial investor playing such a large role within a deal for music IP.

A year later, Michael Jackson, one of the world’s biggest pop stars, reportedly got a heads up from then collaborator Paul McCartney about the value of song catalogs. This led to Jackson in 1985 buying out the catalog of ATV, the British music publisher who not only held rights of The Beatles, but also Bruce Springsteen, The Rolling Stones, Elvis, Little Richard, Hank Williams, and many more in its over four-thousand-track catalog.3William K. Knoedelseder Jr., ‘Music Copyrights Can Be Gold Mines To Current Owners’, Los Angeles Times, 1985-12-29, online: www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1985-12-29-fi-26117-story.html.

Ted Turner, the media magnate that founded the 24-hour news network CNN, desperately wanted to own CBS.4Robert J. Cole, ‘Small Chance Seen For CBS Takeover’, The New York Times, 1985-4-19, online: www.nytimes.com/1985/04/19/business/small-chance-seen-for-cbs-takeover.html. Not satisfied with the niche he had carved in cable news, he wanted to own one of the big three American television networks. He threatened a leveraged buyout of the company but there were not many interested parties in this venture. Still, the threat of a buyout scared CBS enough that they went into massive debt to buy back their own stock to keep Turner away from the company, and thus needed to offload parts of their business to cover the costs.5Geraldine Fabrikant, ‘CBS, Trying To Block Turner Bid, To Buy $1 Billion Of Its Own Stock’, The New York Times, 1985-07-04, online: www.nytimes.com/1985/07/04/business/cbs-trying-to-block-turner-bid-to-buy-1-billion-of-its-own-stock.html. They got rid of much of their print publishing business and in 1986 sold CBS Songs, which was the publishing half of CBS Records, then one of the major labels at the time. A couple years later, CBS would leave the record industry entirely when they would sell CBS Records to Sony.6Paul Richter and William K. Knoedelseder Jr, ‘Sony Buys CBS Record Division For $2 Billion After Months Of Talks’, The New York Times, 1987-11-19, online: www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-11-19-fi-22750-story.html. in a deal helped by a still emerging private equity firm called the Blackstone Group.7Peter J. Boyer, ‘Sony And CBS Records: What A Romance!’, The New York Times Magazine, 1988-9-18, online: www.nytimes.com/1988/09/18/magazine/sony-and-cbs-records-what-a-romance.html. High stakes corporate deals would continue into the 1990s.

In 1990, Matsushita Electric Industrial Co, a Japanese technology company, bought MCA Corp. for $7.5 billion,8Michael Hirsh, “Matsushita Buys MCA In Biggest Japanese Purchase Of U.S. Company”, AP News, 1990-11-26, online: www.apnews.com/article/0a3b82c3c508b4c98e74993e47d52eb2. which alongside Universal Studios and TV shows, included MCA Records. A few years later Seagram would acquire MCA Records and eventually refashion it, after a purchase of Polygram Records in 1998, into Universal Music Group and Universal Music Publishing Group. In 1995, Sony purchased 50% of ATV from Michael Jackson creating Sony/ATV, giving the record label a more sizable publishing arm to stand alongside. The ’90s also started seeing smaller publishing catalogs like that of the famed Motown Records getting picked up by the likes of EMI,9Chuck Philips, “EMI Pays $132 Million For Stake In Catalog Full Of Motown Hits”, Los Angeles Times, 1997-7-2, online: www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-jul-02-fi-8853-story.html. after Berry Gordy, the label founder, already sold the recordings to MCA Records and Boston Ventures in the late 1980s.10James Bates, “Berry Gordy Sells Motown Records For $61 Million”, Los Angeles Times, 1988-6-29, online: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-06-29-fi-4916-story.html.

The consolidation of the recorded music industry paralleled a rise in industry revenues during the late 1990s. The success of the industry’s biggest labels and highest earners overshadowed the downsizing of domestic record label staff and artist rosters, the shrinking of radio stations (particularly in the United States), and a growth towards more global expansion across the then big four record labels of EMI, Universal Music Group, Sony, and Warner. Much less remarked upon is that publishing saw similar, though not quite as dramatic, consolidation during the closing years of the 20th century. By the late ’90s, there were similarly only a handful of major publishers (UMPG, Warner-Chappelle, Sony/ATV, and EMI Publishing). While smaller publishers continued to exist throughout this period, holding on to their catalogs, many of the independent publishers were acquired by the major publishers of the time, much like their counterparts in the record label space. This placed both sides of the music industry within an ever-shrinking number of companies, with many of the companies holding both publishing and recording divisions. This left the music industry looking as if a small group of corporations would own the rights to the vast majority of music IP moving forward. The 20th century began with publishing being the main driver of the music industry. As the ’90s came to a close, publishing was sequestered outside of the dominant narratives about recorded music but, unlike recordings, it was able to withstand the downturn much easier. If the hundreds of millions, and soon to be billions of dollars are spent on publishers, it would be good to best understand all of the various parts of song rights which have increasingly gotten on to the market.

Contextualizing Music Intellectual Property

As the history of this industry has shown, there are a variety of large companies, investment firms, record labels, private investors, publishers, and artists themselves, investing in music IP. However, it can often be very unclear as to what they are buying, what they have rights to, and how they plan to exploit those rights for financial gain. The easiest way to begin to understand this maze of contracts and acquisitions, is to break down music IP into its simplest forms and most traditional allocations.

There are two main IP rights within each recorded song. Each of these rights may be licensed, sold, assigned, and otherwise exploited by its respective owners in a variety of ways. The first of these music IP assets is the copyright in the composition itself, which is the lyrics and melody that make up the song. It can most easily be visualized as the sheet music, as in the notes and lyrics of the song. This is also known as the musical composition or the ‘publishing’. The second music IP asset in each recorded song is the copyright in the specific recording. This is known as the master recording or the ‘master’. It is important to remember that the right to a master is limited to that recording, meaning that if there are five different recordings of the same musical composition, the master recordings may have five different owners, and may each be exploited and licensed separately.

A famous example of this in practice is Taylor Swift re-recording and re-releasing her previous albums. This has the effect of allowing her to own the new masters of her albums, even though she has been unable to purchase the original masters, which were sold to a label by Swift in her original recording contract, and then sold by that label to an investment firm, against the wishes of Swift.11Ryan Mikeala Nguyen, “What Taylor Swift’s Re-recordings Symbolize For Music Ownership’”, New University, 2021-04-12, online: www.newuniversity.org/2021/04/12/what-taylor-swifts-re-recordings-symbolize-for-music-ownership. In this case, both sets of masters are all linked to the same musical compositions and publishing rights, because they are different recordings of the same songs.

There are also some other rights that exist within each recorded song, which may give the creator some additional power depending on the country. In France and many other nations, there are what are known as ‘moral rights’ which exist within each song, and may never be sold. These rights give the original creator a control over how their work is used and credited, even in the case that the IP rights to the music have been sold. Crucially, the United States, where most of these newer IP investors are based, does not have any laws at the moment codifying or protecting moral rights for creators.12“Moral Rights For Musicians: A Primer”, www.futureofmusic.org/blog/2016/05/10/moral-rights-musicians-primer.

In the most basic formulation of music IP ownership, a musician would write their own composition, record it themselves, and self-release it. In this scenario, the musician would own the publishing and the master recording entirely. Recording the composition and releasing it gives the copyright in both to the creator.13“Intro To Music Royalties”, Royalty Exchange, 2021-02-10, online: www.royaltyexchange.com/blog/music-royalties-101-intro-to-royalties.

In the majority of situations, it is not nearly that simple. Often, the songwriting ownership is split between multiple songwriters in a wide variety of percentages. And the people who own the composition are rarely the same people who actually perform the composition on the recording and own the master. There may be multiple songwriters and a larger music group or band that performs and owns the master, or in the case of a cover song, it may be a different group of people entirely. Adding to the complexity, sometimes a producer or recording engineer will own part of the master or publishing in exchange for their work. Each of these people may own a differing piece of a different right, and often (depending on their agreements with others) those are their assets to sell or hold as they would like.

Often the first IP asset to be sold or licensed by a musician is the master recording.14“What Does It Mean To Own Your Masters?”, amuse, online: www.amuse.io/en/content/owning-your-masters. Musicians will sign recording deals with labels in exchange for selling the ownership of masters to the label (or licensing them exclusively for a set period). As part of these deals, the musician will receive a payment and some form of royalty from the future exploitation of the masters. Almost always, these deals require the musician to sell or license the master recordings in their entirety, which is why few artists still maintain ownership over their master recordings.

Directly behind the master recording, publishing is still something that the majority of songwriters pursue. Publishing deals are structured similarly to record label deals,15Cliff Goldmacher, “The Pros & Cons Of Signing A Publishing Deal”, BMI, 2010-05-25, online: www.bmi.com/news/entry/the_pros_cons_of_signing_a_publishing_deal. where in exchange for the sale (or long-term exclusive license) of compositions, the songwriter will receive a payment and some form of future royalties, along with the assurance that the publisher will do their best to promote, license, and otherwise increase the value of the compositions. However, unlike with masters, there are some protections for songwriters that prevent them from selling the entirety of their composition in many circumstances. By law in the United States, and through similar laws elsewhere throughout the world (including France), a publisher is only allowed to purchase or license 50 percent of a composition. Therefore, most songwriters are in a publishing deal that gives their publisher ownership of 50 percent of their compositions, known as the ‘publisher’s share’, while the artists themselves maintain the remaining 50 percent, which is known as the ‘writer’s share’.

Over the course of these many deals, sales, and licenses, the rights that make up these music IP assets are spread in many directions, which has a confusing and disorientating effect for creators especially. A creator may sell their publishing and masters all in a single deal to one entity, or in many deals over the course of their career. These new owners may then sell some or all of their assets to other investors, who may sell or even sub-license those assets to other investors. It is in this environment, where music IP assets are frequently sold and traded, that we see private equity increasing their push into this sector, which as we have found, has had a very substantial effect.

It is also important to recognize that it is not a coincidence that these sales of masters and publishing seem to have accelerated in the 2010s, and especially in the 2020s, as songwriters’ and artists’ incomes have plummeted, first during the streaming era, and now even more so during the COVID pandemic. In these times, artists and songwriters and other music IP owners have become more desperate for capital, and more willing to sell these remaining assets.

Generating Revenue with Music Intellectual Property

When music companies or investors buy an artist’s IP, what they are actually purchasing is some variety of master and publishing rights. Sometimes this means that they have purchased the entire ownership of those masters and compositions, but not necessarily. These purchases may be limited in a variety of ways. Perhaps the purchaser has all rights to the music IP subject to certain restrictions, or only owns a small percentage of the IP, or doesn’t own the IP at all, but owns the rights to all of the revenue generated by that IP. The terms and conditions of these arrangements are often confidential as well, further obscuring the true situation.

While it is often hard to find out the true nature of these deals to purchase music IP, what we do know for sure is that these purchasers are using every effort possible to exploit their newly purchased IP and generate revenue that more than makes up for their purchase price. The owner of the master recording is paid whenever that recording is sold (on a physical medium like vinyl or CD, or a digital medium like an mp3) or performed (via a streaming service, radio, synchronization with a film, etc.). Because the composition is the melody and lyrics that make up the song, the owner of the composition is paid whenever any master containing the composition is sold (on a physical medium like vinyl or CD, or a digital medium like an mp3) or performed (via a streaming service, radio, synchronization with a film, etc.).

While music IP owners are continuing to pursue the traditional revenue areas, newer IP investors have particularly taken advantage of emerging new markets as well. In fact, the excitement around the diversity of ways to profit from music IP in the modern entertainment economy, may be one of the things that is driving the increase in purchases. Over the last few years, there has been a rise in ways to monetize an artist’s IP, including deals with social media companies, workout apps, video games, and other industries that have become interested in licensed music.

These newer forms of music IP agreements are often announced but little context is provided about how artists are being paid for their works. These revenue streams, which include fitness apps such as Peloton, social media apps such as TikTok and Instagram, and pandemic-friendly live streaming performances on Twitch and YouTube, are likely resulting in favorable deals for music publishers, major labels and the other owners of the music IP. In the case of fitness apps, a business of which grew 53% to reach $4.4 billion in 2020 according to Grand View Research,16“Fitness App Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report”, Grand View Research, online: www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/fitness-app-market. this music is presumably licensed similar to that of a film or advertising synchronization license which generally see a 50/50 split between labels and publishers. Cover versions of songs are also especially popular in music synchronization placements, which further favor the owners of publishing rights specifically, because cover songs allow the licensor to avoid paying the master owners of the original recording.

While there are many new ways to profit off of music IP ownership, it isn’t only new masters and compositions that are benefiting. In fact, older songs, which are referred to as ‘legacy catalog’, have also seen an uptick in attention and profitability. This is largely due to the viral nature of TikTok, Instagram, and other social media sites, which are able to bring well known songs from the past back into the spotlight. TikTok alone has thrust artists from Fleetwood Mac to The B-52s into viral content that has put the songs in front of a new generations of fans.17Bobby Allyn, “Tiktok Sensation: Meet The Idaho Potato Worker Who Sent Fleetwood Mac Sales Soaring”, NPR, 2020-10-11, online: www.npr.org/2020/10/11/922554253/tiktok-sensation-meet-the-idaho-potato-worker-who-sent-fleetwood-mac-sales-soari. While the nature of TikTok’s music licensing deals is largely unknown, the platform and its often nostalgia-driven trends are sure to drive revenues for publishing and master rights holders as songs (re)gain popularity and are consumed across streaming and social media platforms.

Though less future-proof than the rise of music licensing fitness apps and viral social media hits, music live streaming cannot be overlooked as a new revenue stream for music IP rights holders. As pandemic restrictions rise and fall across the world in the coming months, it seems that both the return of live music, accompanied by the live streaming business, will prove advantageous to those holding publishing rights and other IP required for the performances.18Will Page, “Global Value Of Music Copyright Up 2.7% To $32.5bn In 2020”, 2021-11-16, online: www.tarzaneconomics.com/undercurrents/copyright-2021.

While the growing diversification of revenue-generating activities can certainly be cited as a reason for new and increasing financial interest in song right acquisition, it is important to address that these trends will have different impacts depending on which rights the purchaser is acquiring. When studying the financialization and purchases of music IP, it is very difficult for anyone but the parties involved to know exactly what assets are being purchased and to what extent. Different purchasers are interested in different rights, and wish to pursue them to different ends. Some investors are mostly interested in buying IP based on the revenue they think those assets will generate, but do not want to fulfill the duties of a record label or music publisher to market and sell these assets, and instead sublicense those duties to a major label or publisher. Other buyers are purchasing masters from a wide variety of labels and artists and are assembling a large record label infrastructure, as we have seen with Round Hill.19Murray Stassen, “Round Hill Records Buys More Masters, Makes New Hires And Opens Nashville HQ”, Music Business Worldwide, 2021-06-16, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/as-round-hill-buys-more-masters-the-company-makes-new-hires-and-launches-nashville-hq. Still, others are serving instead as large-scale music publishers and buying compositions and assets from music publishing companies. There are also some buyers which are doing a combination, or changing their focus year to year. It is important to note that whether the buyers are purchasing the rights to the master or the composition, these purchases give them a substantial amount of power over how this IP is used. It is very foreseeable that they will almost always use this power to purely generate profit that will fulfill the purpose of their investment.

21st Century Sales of Music Catalogs

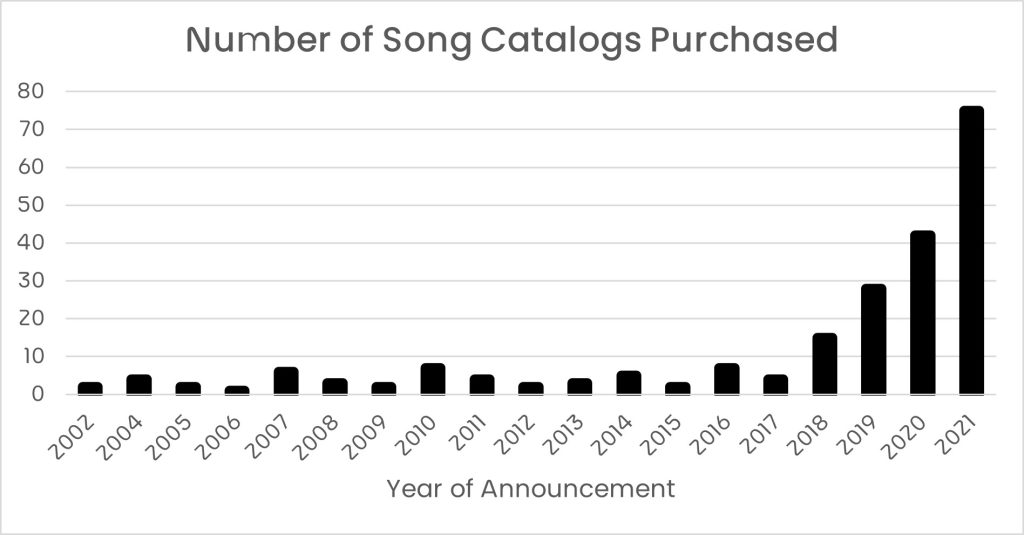

Since the rock-and-roll boom in the 1960s, which in turn led to the record music industry becoming a billion, then multi-billion dollar industry, there has been an underrated but well understood value in music publishing. However in the early 2000s, a number of financial institutions – ranging from traditional banks to multi-trillion dollar asset managers – began creeping into a part of the industry that was often considered to be the less exciting corner of the business. The research in this report explicitly looked at purchases that were reported in the press from 2001 to 2021 to get a sense of the trends shaping this space. The graph below shows that over the last two decades there has been a sharp increase in the number of music catalog purchases. (This graph does not include record labels or publishers that own catalogs.)

At the turn of the millennium, these purchases were concentrated within a handful of companies and financial backers. The Royal Bank of Scotland and the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, one of the largest Québec-based pension funds, were early investors. The former purchased Chrysalis PLC UK for over £60 million20Vinod Kothari Consultants, online: www.vinodkothari.com/ipsecur. and the latter invested over $30 million into Mosaic Music Publishing from 2000 to 2001.21“Former Aerosmith Managers Sell Rights To Band’s Catalog”, Blabbermouth, 2002-08-14, online: www.blabbermouth.net/news/former-aerosmith-managers-sell-rights-to-band-s-catalog. The private equity firm Apax Partners bought Stage Three Music, a music publisher, for over £40 million in 2004, and a year later Stage Three Music would acquire Mosaic Music Publishing.22“U.K.’s Stage Three Picks Up Mosaic Catalog”, Billboard, 2005-04-04, online: www.billboard.com/music/music-news/uks-stage-three-picks-up-mosaic-catalog-1414827. The companies involved in the early 2000s would not continue to make the same flashy headlines as those that followed in their footsteps and very quickly began to dominate this still relatively underexplored market.

Our research shows a lull in music catalog and publisher acquisitions in 2005 and 2006. Primary Wave, a private equity company, made its first big-name purchase with the Nirvana catalog in 2006.23Jolie Lash, “Courtney Love Sells Nirvana Rights Share”, Rolling Stone, le 3.30.2006, online: www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/courtney-love-sells-nirvana-rights-share-101726. The company followed up that purchase with fellow rock legends Hall and Oates24Peter Lauria, “Private Eyes Focus On Hall & Oates Catalog”, New York Post, 2007-02-01, online: www.nypost.com/2007/02/01/private-eyes-focus-on-hall-oates-catalog. and John Lennon,25“Julian Lennon Sells Stake In Beatles Songs”, Reuters, 2007-04-13, online: www.reuters.com/article/us-beatles-lennon/julian-lennon-sells-stake-in-beatles-songs-report-idUSN1340484820070413. which made 2007, till that point, the busiest year for reported music purchases. Happening alongside the global financial crisis, a sudden rush of money starts to enter into these deals: Stichting Pensioenfonds ABP, a Dutch pension fund, bought the catalog of the Rodgers and Hammerstein Estate for over $200 million,26Yinka Adegoke, “Music Publishing’s Steady Cash Lures Investors”, Reuters, 2009-04-23, online: www.reuters.com/article/us-publishing-analysis/music-publishings-steady-cash-lures-investors-idUSTRE53M6TK20090423. the second largest purchase in this space only after the same pension fund helped purchase the publishers Boosey & Hawkes for nearly a quarter of a billion dollars.27“Pension Fund ABP Buys Music Assets In $250 Mln Deal”, Reuters, 2008-04-11, online: www.reuters.com/article/abp/update-1-pension-fund-abp-buys-music-assets-in-250-mln-deal-idUSL1190066120080411.

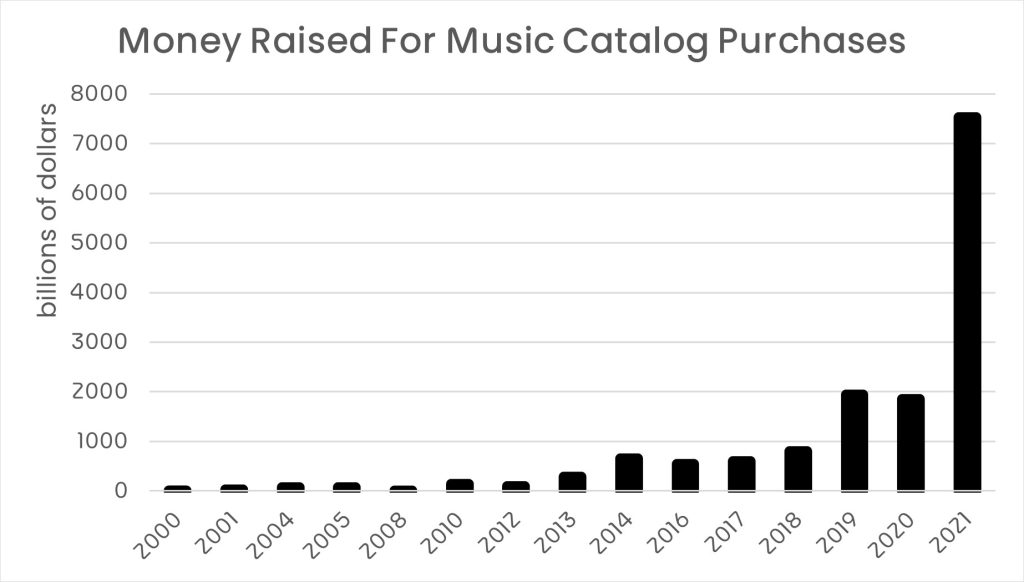

The early 2010s saw a relatively steady number of catalog purchases happening. There started to emerge more attention and money around this particular market, as new firms like Round Hill Music, Kobalt Capital, and Concord Music Group were appearing. These companies continued the model established by Primary Wave, of raising money from deep pocketed investors all in pursuit of artist catalogs. RPMI Railpen, a pension fund for railway workers in the United Kingdom, gave $600 million to Kobalt Capital in 2017,28Andre Paine, “Kobalt Capital closes $600 million investment fund”, Music Week, 2017-11-06, online: www.musicweek.com/publishing/read/kobalt-capital-closes-600-million-investment-fund/070382. and SunTrust Bank raised money for both Primary Wave and Roundhill. These newer firms along with more established players like Primary Wave and Spirit Music Group were accounting for a majority of reported purchases between 2010 and 2017. During these years at least $2.6 billion was raised to help purchase catalogs. This represented over ten times the amount of reported money raised from 2000 to 2009, and those numbers would only accelerate upwards towards the end of the decade, as seen in the graph below.

In July of 2018, the Hipgnosis Songs Fund, led by Merck Mercuriadis, the former manager of Beyoncé, Pet Shop Boys, Elton John, and Guns N’ Roses, made its first public purchase of The-Dream’s catalog.29Tim Ingham, “Merck Mercuriadis Fund Pays $23M To Buy 75% Stake In The-Dream Catalog”, Music Business Worldwide, 2018-07-11, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/merck-mercuriadis-fund-pays-23m-to-buy-majority-stake-in-the-dream-catalog. The company wasted no time quickly buying up as many catalogs as it could and making sure to publicize the purchases. According to Hipgnosis’ own financial statements, which include non-public reported deals, they made six catalog purchases in 2018; thirty-eight in 2019; and forty-two in 2020.30www.hipgnosissongs.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/HSFL-AR21-web.pdf. These numbers far outpace other firms within the space, even though few other companies reveal purchases that were not announced in the press. This is important to note for understanding this market: while many deals are accompanied with press releases, judging by Hipgnosis’s example, there are certainly many more deals happening underneath all radars. Below is a graph that shows the split between public reported purchases by the company and what is fully captured by their own financial statements.

Since the late 2010s, the biggest shift in the market is the arrival of larger institutional investing firms. In 2016, Primary Wave received $300 million in a deal with the asset manager BlackRock that helped them purchase the catalog of R&B singer Smokey Robinson.31Andy Gensler, “Primary Wave’s CEO Explains A New $300 Million Blackrock Partnership, Getting Smokey Robinson A Sneaker Deal”, Billboard, 2016-09-28, online: www.billboard.com/music/music-news/primary-wave-larry-mestel-smokey-robinson-300-million-blackrock-partnership-7525653. In 2021, the Blackstone Group and Apollo Global Management both raised a billion dollars for Hipgnosis and HarbourView Equity Partners respectively.32Ben Sisario, “A $1 Billion Competitor for Music Rights Says ‘Content Is Queen’”, The New York Times, 2021-10-07, online: www.nytimes.com/2021/10/07/arts/music/sherrese-clarke-soares-harbourview.html. Not to be left out, BMG reconnected with the private equity firm KKR to raise a billion dollars for acquisitions,33Tim Ingham, “BMG And KKR Are Ready To Spend $1bn On Music Copyrights, And That’s Just For Starters…”, Music Business Worldwide, 2021-04-06: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/bmg-and-kkr-are-ready-to-spend-1bn-on-music-copyrights-and-thats-just-for-starters. and in early 2022 agreed to do a deal with Pimco, an investment bank with over $2.6 trillion in assets.34Murray Stassen, “Pimco, One Of The World’s Biggest Investment Firms, Turns Its Attention To Music Rights”, Music Business Worldwide, 2022-01-14, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/pimco-one-of-the-worlds-biggest-investment-firms-turns-its-attention-to-music-rights. The monetary scale of these deals is what really separates them from previous pension fund and private equity investment in this space. So far, few of these deals show an aggressively active hand on the part of these large financial institutions. Rather, they appear to be targeting working with already established representatives in the industry, who might be able to better navigate what is becoming a more competitive market. The arrival of these larger institutional investors right now has not produced a different kind of investment strategy for music catalog, but rather, shows a continuation of what many private equity and pension funds have been doing over the last two decades. It differs slightly from where major labels and publishers are beginning to enter into the market.

Not to be left out of the mix, the world’s biggest publishers (Warner Chappell, Sony Music Publishing, and Universal Music Group Publishing) are now getting more involved in this market. One should not misread that major labels were caught sleeping, because the vast majority of successful performers are still signed to major publishing deals. Still, it was until the last few years that such big-name deals by major labels over catalog jumped from the trade magazine back pages into headlines reaching more casual music fans. Warner Music Group was early to shift by partnering with Providence, a private equity firm, to form Tempo Music Investments which initially raised $650 million.35Jem Aswad, “Warner Music, Providence Equity Launch $650 Million Fund To Invest In Song Catalogs”, Variety, 2019,-12–10 online: www.variety.com/2019/biz/news/warner-music-providence-equity-jeff-bhasker-shane-mcanally-1203431271. The arrangement was not apparent enough for the company, as they went ahead and made other deals with the likes of David Bowie, without entangling their outside cash flow.36See the press release of January 3, 2022: www.wmg.com/news/warner-chappell-acquires-david-bowie-music-publishing-catalog-36046. Additional major classic rock purchases include Bob Dylan’s publishing catalog by Universal Music Publishing Group,37Tim Ingham, “Universal Buys Bob Dylan Publishing Rights, Acquiring Catalog Worth Hundreds Of Millions Of Dollars”, Music Business Worldwide, 2020-12-07, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/universal-buys-bob-dylan-publishing-rights-acquiring-catalog-worth-hundreds-of-millions-of-dollars. and Sony picking up Dylan’s recordings38Murray Stassen, ”Sony Music Acquires Bob Dylan’s Recorded Music Catalog”, Music Business Worldwide, 2022-01-24, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/sony-music-acquires-bob-dylans-recorded-music-catalog11111. and Bruce Springsteen’s both recordings and publishing with additional financing by Eldridge Industries to help on the latter purchase.

What has emerged over the last five years is an effective arms race between older firms, which have been acquiring catalogs since the 2000s, against now very well-financed major labels, which are unafraid to take outside financial cash, and newer companies that are often staffed by former employees and executives of the latter two groups. The difference is that newer firms like Hipgnosis are often far more lean than traditional music publishers. Billboard reported the company technically does not even have any employees and that much of the administration work for these songs is left to the labels, who were often the original owners of the music.39 Glenn Peoples, “Inside Hipgnosis Songs’ Mid-Year Report”, Billboard, 12.20.2021, online: www.billboard.com/pro/hipgnosis-songs-mid-year-report-2021. Otherwise, there isn’t any particular throughline in the types of catalogs, whether by age or genre, that are being consumed by these various kinds of firms or financial actors. Most of these companies are centered on English-speaking music that has proven to make money, which may explain why the market for catalog acquisitions looks markedly different in France and continental Europe.

The European Music Catalog Acquisition Landscape

British and US-based firms are the primary investors for musician catalogs, but Europe – including France – is beginning to see similar trends play out. The centrality of English-speaking companies can be seen in the United States and the United Kingdom being two of the largest recorded music markets and there already being a healthy history of buying and selling musicians’ works. Those dynamics aren’t always repeated across Europe. A 2019 report by the Chambre syndicale des Éditeurs de Musique de France estimated that major labels only represent 46% of the market,40See in French, “Baromètre de l’édition musicale 2019”, online: www.musiquesactuelles.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/barometre-2019-def.pdf. compared to other western markets where major labels own a clear majority of the market. The relative strength of local publishers and the differences between copyright law amongst the country has not quite allowed the same firms to go on purchasing sprees with French or Swedish catalogs. Still, there has been a growing move towards this direction over the last fifteen years.

In 2007, the German media conglomerate Bertelsmann sold BMG Music Publishing to Universal Music Group for nearly $2.19 billion, helping further situate UMPG as one of the world’s dominant music publishers.41Yinka Adegoke, “Universal Music Closes On BMG”, Reuters, 2007-05-25, online: www.reuters.com/article/industry-universal-bmg-dc/universal-music-closes-on-bmg-idUKN2524635320070525. This effectively left Bertelsmann nearly out of the music business, having already sold off its recording arm to Sony earlier in the decade during the industry wide recession. However, the company wasn’t completely out: in 2009 it took a 51% investment from private equity firm KKR with the mission of helping build back its publishing business. The next year, BMG bought from the catalogs of the French songwriters Louis Chedid42“BMG Acquires Editions Louis Chedid”, 2010-03-16, online: www.bmg.com/de/news/bmg-acquires-editions-louis-chedid.html. and Gérald De Palmas.43Robert Ashton, “De Palmas Goes To BMG”, Music Week, 2010-01-26, online: www.musicweek.com/news/read/de-palmas-goes-to-bmg/041712. These purchases, along with Imagen (backed by a Dutch pension fund) buying up part of Universal Music Publishing Group and Boosey & Hawkes, shows there is a buzz within Europe to seek out these assets.44“Pension Fund ABP Buys Music Assets In $250 Mln Deal”, Reuters, 2008-04-11, online: www.reuters.com/article/abp/update-1-pension-fund-abp-buys-music-assets-in-250-mln-deal-idUSL1190066120080411. However, KKR sold its shares of BMG Rights Management back to Bertelsmann in 2013, but in 2021 the two companies reconnected to raise over a billion dollars for a more mature song catalog market.

While BMG’s company history dates back to the mid-19th century, a number of newer companies are looking to break into this niche. Kilometre Music Group announced raising $200 million from Barometer Capital Management Inc., a Toronto-based investment firm with the explicit aim of seeking out work from Canadian songwriters, though they have expanded outside with certain early purchases.45Karen Bliss, “New Canadian Venture Is Banking On Bringing Copyrights Back North”, Billboard, 2021-02-18, online: www.billboard.com/pro/canadian-copyright-fund-michael-mccarty-kilometre-music-group. Pythagoras Music Fund brought in $117 million from an undisclosed number of institutional and private Dutch investors.46Murray Stassen, “$117 M Fund Launches In Europe To Buy Catalogs Of Local Legends”, Music Business Worldwide, 2021-09-22, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/117m-fund-launches-in-europe-to-buy-catalogs-of-local-legends. In early 2022, the electronic music trio Swedish House Mafia announced selling their master recordings and publishing rights to PopHouse, a Swedish entertainment company co-founded by members of ABBA.47Murray Stassen, “Swedish House Mafia Sell Master Recordings And Publishing Catalogs To Pophouse”, Music Business Worldwide, 2022-03-29, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/swedish-house-mafia-sell-master-recordings-and-publishing-catalogs-to-pophouse. The ubiquity of languages like English, French, and Spanish would likely tilt investor interests towards works that are going to be able to reach more people (via playlists, synch deals, etc.). Still, early signs show there is plenty of fertile ground to be sowed for companies looking to carve out a niche within this space. The possibilities of European, and in particular French, catalogs being susceptible to the same trajectory of American and British artists is where this report will end, on what may lay next for this market.

Conclusion

A troubling implication of increased business activity and liquidity in the song catalog market is the illusion of a prosperous industry. While the price tags on publishing catalogs draw headlines and flow money back into major publishers and high-profile artists’ pockets, this is not the reality for most. Song rights management companies like Hipgnosis Songs Management invest in catalogs which have proven track records and chart-topping success, with which they hope to extract more value via anniversary box sets, viral mashups and blockbuster sync placements. Just as 1% of songs on Spotify account for 90% of streams, private catalog purchases privilege an elite tier of artists.48Emily Blake, “Data Shows 90 Percent Of Streams Go To The Top 1 Percent Of Artists”, Rolling Stone, 2020-09-09, online: www.rollingstone.com/pro/news/top-1-percent-streaming-1055005. This privileging of hitmakers has considerable knock-on effects for artists lower down the food chain. In filings dated October 2021, both Spotify and Apple cited recent publishing catalog purchases as an indicator to the United States Copyright Royalty Board that the copyright fees interactive streaming companies pay to rights holders should be set to the lowest rate in history.49www.app.crb.gov/document/download/25876 & www.app.crb.gov/document/download/25856. That the sales of objectively few, already well-performing catalog sales could influence the amount which all artists are paid for the consumption of their music indicates increased hegemonic control, not the health of the industry at large. Those benefiting most from the music publishing and copyrights are private-equity backed firms and publicly-listed technology companies, not the artists themselves.

While the interest of private equity firms in music catalogs should sound alarm bells for those not involved in the production of hit-making music, their interest in music as an asset class could prove interesting for valuations of music catalogs, and the music industry at large moving forward. In the mid-2000s, streaming and digital file sharing discouraged investors and, in the specific example of David Bowie’s Bowie Bonds, saw them liken music bonds once known for their stability to that of a junk bond rating. Though Bowie Bonds did mature and redeem in 2007, at which point Bowie regained control of his catalog, the investment program is widely seen as a failure due to the low investment grade the bonds eventually received.50James Chen, “Bowie Bond”, Investopedia, 2022-07-31, online: www.investopedia.com/terms/b/bowie-bond.asp. Yet, only 15 years later, Bowie’s same catalog was valued at $250 million when sold to Warner Chappell Music in January 2022. This return to music as an asset class with a predictable rate of return bodes well for others looking to sell catalog, and a shift away from the traditional publishing industry offering could embolden new players and introduce diversity in the publishing space.

That new buyers are entering the market has somewhat divested major labels from their total grip on publishing rights. Perhaps this diversity in institutional investors could lead to a localized approach in catalog purchases, as seen with funds raised and purchasing firms established in both the Canadian and Dutch markets. It also seems advantageous that municipal and national governments begin to invest in homegrown talent as a means of generating capital and perpetuating culture. If music can be valued not only as a capital investment, but also a civic and cultural investment, the acquisition of music catalogs could prove a means of stimulating production and preserving heritage. If the financial gains generated by song catalogs were to then be invested back into local or regional musical artists and industries, value would be accumulated both monetarily and culturally on a scale which would serve to benefit artists outside of the global mainstream.

The recognition of alternative publishing ownership models and the general value of the music industry as an attractive space for investors will have trickle down effects to artists both in and outside of the hit-making, English-speaking market – just what those effects are is difficult to predict. On one hand, music catalog value could continue to go up due to market demand and increased value of publishing rights, catalog buyers and their purchases could get more niche and diverse, and money could increasingly flow to artists through these sales. On the other, the speed and size of catalog sales could slow and shrink with rising interest rates over the next few years, investors could continue to only purchase hit-making catalogs, and artists could increasingly be stripped of the long-term agency to determine how their music is exploited.51Lucas Shaw, “The Music Catalog Boom May Be Coming To An End”, Bloomberg, 2022-04-04, online: www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-04-03/the-music-catalog-boom-may-be-coming-to-an-end. Unfortunately, if current financial market trends and the tendency of the music industry to consolidate its business activity are anything to go by, the latter scenario is more likely.

- 1Irv Litchman, ‘Oldline Publishing Firm E.B. Marks Music Sold’, Billboard, 1983-03-12, p74, online: www.worldradiohistory.com/Archive-All-Music/Billboard/80s/1983/BB-1983-03-12.pdf.

- 2Sandra Salmans, ‘A Song Plugger’s Biggest Play: His Return As Boss’, The New York Times, 1985-06-04, online: www.nytimes.com/1985/06/04/business/new-yorkers-co-a-song-plugger-s-biggest-play-his-return-as-boss.html.

- 3William K. Knoedelseder Jr., ‘Music Copyrights Can Be Gold Mines To Current Owners’, Los Angeles Times, 1985-12-29, online: www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1985-12-29-fi-26117-story.html.

- 4Robert J. Cole, ‘Small Chance Seen For CBS Takeover’, The New York Times, 1985-4-19, online: www.nytimes.com/1985/04/19/business/small-chance-seen-for-cbs-takeover.html.

- 5Geraldine Fabrikant, ‘CBS, Trying To Block Turner Bid, To Buy $1 Billion Of Its Own Stock’, The New York Times, 1985-07-04, online: www.nytimes.com/1985/07/04/business/cbs-trying-to-block-turner-bid-to-buy-1-billion-of-its-own-stock.html.

- 6Paul Richter and William K. Knoedelseder Jr, ‘Sony Buys CBS Record Division For $2 Billion After Months Of Talks’, The New York Times, 1987-11-19, online: www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-11-19-fi-22750-story.html.

- 7Peter J. Boyer, ‘Sony And CBS Records: What A Romance!’, The New York Times Magazine, 1988-9-18, online: www.nytimes.com/1988/09/18/magazine/sony-and-cbs-records-what-a-romance.html.

- 8Michael Hirsh, “Matsushita Buys MCA In Biggest Japanese Purchase Of U.S. Company”, AP News, 1990-11-26, online: www.apnews.com/article/0a3b82c3c508b4c98e74993e47d52eb2.

- 9Chuck Philips, “EMI Pays $132 Million For Stake In Catalog Full Of Motown Hits”, Los Angeles Times, 1997-7-2, online: www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-jul-02-fi-8853-story.html.

- 10James Bates, “Berry Gordy Sells Motown Records For $61 Million”, Los Angeles Times, 1988-6-29, online: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-06-29-fi-4916-story.html.

- 11Ryan Mikeala Nguyen, “What Taylor Swift’s Re-recordings Symbolize For Music Ownership’”, New University, 2021-04-12, online: www.newuniversity.org/2021/04/12/what-taylor-swifts-re-recordings-symbolize-for-music-ownership.

- 12“Moral Rights For Musicians: A Primer”, www.futureofmusic.org/blog/2016/05/10/moral-rights-musicians-primer.

- 13“Intro To Music Royalties”, Royalty Exchange, 2021-02-10, online: www.royaltyexchange.com/blog/music-royalties-101-intro-to-royalties.

- 14“What Does It Mean To Own Your Masters?”, amuse, online: www.amuse.io/en/content/owning-your-masters.

- 15Cliff Goldmacher, “The Pros & Cons Of Signing A Publishing Deal”, BMI, 2010-05-25, online: www.bmi.com/news/entry/the_pros_cons_of_signing_a_publishing_deal.

- 16“Fitness App Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report”, Grand View Research, online: www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/fitness-app-market.

- 17Bobby Allyn, “Tiktok Sensation: Meet The Idaho Potato Worker Who Sent Fleetwood Mac Sales Soaring”, NPR, 2020-10-11, online: www.npr.org/2020/10/11/922554253/tiktok-sensation-meet-the-idaho-potato-worker-who-sent-fleetwood-mac-sales-soari.

- 18Will Page, “Global Value Of Music Copyright Up 2.7% To $32.5bn In 2020”, 2021-11-16, online: www.tarzaneconomics.com/undercurrents/copyright-2021.

- 19Murray Stassen, “Round Hill Records Buys More Masters, Makes New Hires And Opens Nashville HQ”, Music Business Worldwide, 2021-06-16, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/as-round-hill-buys-more-masters-the-company-makes-new-hires-and-launches-nashville-hq.

- 20Vinod Kothari Consultants, online: www.vinodkothari.com/ipsecur.

- 21“Former Aerosmith Managers Sell Rights To Band’s Catalog”, Blabbermouth, 2002-08-14, online: www.blabbermouth.net/news/former-aerosmith-managers-sell-rights-to-band-s-catalog.

- 22“U.K.’s Stage Three Picks Up Mosaic Catalog”, Billboard, 2005-04-04, online: www.billboard.com/music/music-news/uks-stage-three-picks-up-mosaic-catalog-1414827.

- 23Jolie Lash, “Courtney Love Sells Nirvana Rights Share”, Rolling Stone, le 3.30.2006, online: www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/courtney-love-sells-nirvana-rights-share-101726.

- 24Peter Lauria, “Private Eyes Focus On Hall & Oates Catalog”, New York Post, 2007-02-01, online: www.nypost.com/2007/02/01/private-eyes-focus-on-hall-oates-catalog.

- 25“Julian Lennon Sells Stake In Beatles Songs”, Reuters, 2007-04-13, online: www.reuters.com/article/us-beatles-lennon/julian-lennon-sells-stake-in-beatles-songs-report-idUSN1340484820070413.

- 26Yinka Adegoke, “Music Publishing’s Steady Cash Lures Investors”, Reuters, 2009-04-23, online: www.reuters.com/article/us-publishing-analysis/music-publishings-steady-cash-lures-investors-idUSTRE53M6TK20090423.

- 27“Pension Fund ABP Buys Music Assets In $250 Mln Deal”, Reuters, 2008-04-11, online: www.reuters.com/article/abp/update-1-pension-fund-abp-buys-music-assets-in-250-mln-deal-idUSL1190066120080411.

- 28Andre Paine, “Kobalt Capital closes $600 million investment fund”, Music Week, 2017-11-06, online: www.musicweek.com/publishing/read/kobalt-capital-closes-600-million-investment-fund/070382.

- 29Tim Ingham, “Merck Mercuriadis Fund Pays $23M To Buy 75% Stake In The-Dream Catalog”, Music Business Worldwide, 2018-07-11, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/merck-mercuriadis-fund-pays-23m-to-buy-majority-stake-in-the-dream-catalog.

- 30

- 31Andy Gensler, “Primary Wave’s CEO Explains A New $300 Million Blackrock Partnership, Getting Smokey Robinson A Sneaker Deal”, Billboard, 2016-09-28, online: www.billboard.com/music/music-news/primary-wave-larry-mestel-smokey-robinson-300-million-blackrock-partnership-7525653.

- 32Ben Sisario, “A $1 Billion Competitor for Music Rights Says ‘Content Is Queen’”, The New York Times, 2021-10-07, online: www.nytimes.com/2021/10/07/arts/music/sherrese-clarke-soares-harbourview.html.

- 33Tim Ingham, “BMG And KKR Are Ready To Spend $1bn On Music Copyrights, And That’s Just For Starters…”, Music Business Worldwide, 2021-04-06: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/bmg-and-kkr-are-ready-to-spend-1bn-on-music-copyrights-and-thats-just-for-starters.

- 34Murray Stassen, “Pimco, One Of The World’s Biggest Investment Firms, Turns Its Attention To Music Rights”, Music Business Worldwide, 2022-01-14, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/pimco-one-of-the-worlds-biggest-investment-firms-turns-its-attention-to-music-rights.

- 35Jem Aswad, “Warner Music, Providence Equity Launch $650 Million Fund To Invest In Song Catalogs”, Variety, 2019,-12–10 online: www.variety.com/2019/biz/news/warner-music-providence-equity-jeff-bhasker-shane-mcanally-1203431271.

- 36See the press release of January 3, 2022: www.wmg.com/news/warner-chappell-acquires-david-bowie-music-publishing-catalog-36046.

- 37Tim Ingham, “Universal Buys Bob Dylan Publishing Rights, Acquiring Catalog Worth Hundreds Of Millions Of Dollars”, Music Business Worldwide, 2020-12-07, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/universal-buys-bob-dylan-publishing-rights-acquiring-catalog-worth-hundreds-of-millions-of-dollars.

- 38Murray Stassen, ”Sony Music Acquires Bob Dylan’s Recorded Music Catalog”, Music Business Worldwide, 2022-01-24, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/sony-music-acquires-bob-dylans-recorded-music-catalog11111.

- 39Glenn Peoples, “Inside Hipgnosis Songs’ Mid-Year Report”, Billboard, 12.20.2021, online: www.billboard.com/pro/hipgnosis-songs-mid-year-report-2021.

- 40See in French, “Baromètre de l’édition musicale 2019”, online: www.musiquesactuelles.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/barometre-2019-def.pdf.

- 41Yinka Adegoke, “Universal Music Closes On BMG”, Reuters, 2007-05-25, online: www.reuters.com/article/industry-universal-bmg-dc/universal-music-closes-on-bmg-idUKN2524635320070525.

- 42“BMG Acquires Editions Louis Chedid”, 2010-03-16, online: www.bmg.com/de/news/bmg-acquires-editions-louis-chedid.html.

- 43Robert Ashton, “De Palmas Goes To BMG”, Music Week, 2010-01-26, online: www.musicweek.com/news/read/de-palmas-goes-to-bmg/041712.

- 44“Pension Fund ABP Buys Music Assets In $250 Mln Deal”, Reuters, 2008-04-11, online: www.reuters.com/article/abp/update-1-pension-fund-abp-buys-music-assets-in-250-mln-deal-idUSL1190066120080411.

- 45Karen Bliss, “New Canadian Venture Is Banking On Bringing Copyrights Back North”, Billboard, 2021-02-18, online: www.billboard.com/pro/canadian-copyright-fund-michael-mccarty-kilometre-music-group.

- 46Murray Stassen, “$117 M Fund Launches In Europe To Buy Catalogs Of Local Legends”, Music Business Worldwide, 2021-09-22, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/117m-fund-launches-in-europe-to-buy-catalogs-of-local-legends.

- 47Murray Stassen, “Swedish House Mafia Sell Master Recordings And Publishing Catalogs To Pophouse”, Music Business Worldwide, 2022-03-29, online: www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/swedish-house-mafia-sell-master-recordings-and-publishing-catalogs-to-pophouse.

- 48Emily Blake, “Data Shows 90 Percent Of Streams Go To The Top 1 Percent Of Artists”, Rolling Stone, 2020-09-09, online: www.rollingstone.com/pro/news/top-1-percent-streaming-1055005.

- 49

- 50James Chen, “Bowie Bond”, Investopedia, 2022-07-31, online: www.investopedia.com/terms/b/bowie-bond.asp.

- 51Lucas Shaw, “The Music Catalog Boom May Be Coming To An End”, Bloomberg, 2022-04-04, online: www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-04-03/the-music-catalog-boom-may-be-coming-to-an-end.