Introduction

In July 2022, the American online magazine Paste went with the headline “The Kids Aren’t Alright : Inside Gen Z’s Chaotic Introduction to Live Music.”1Leila Jordan, “The Kids Aren’t Alright: Inside Gen Z’s Chaotic Introduction to Live Music,” Paste Magazine, 2022-07-14, https://www.pastemagazine.com/music/gen-z-concert-safety/. The article took a look back at the “chaotic introduction” to summer festivals for “hordes of Gen Z teenagers” without any concert experience, after two years of health restrictions and cancellations due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This portrait may seem surprising. For a long time, the close relationship maintained between live music — festivals in particular — and young people seemed obvious, even like a constituent element of the very essence of pop.2For further discussion on this topic, see Agnès Gayraud, Younger Than Yesterday: Jeunesse pop à travers les âges, 2023-01-03, https ://www.theravingage.com/documents/gayraud-younger-than-yesterday.On the contrary, when it came to age, the issue seemed to focus more on those who continued to go to concerts despite their advancing age.3Andy Bennett, “Punk’s not Dead: The Continuing Significance of Punk Rock for an Older Generation of Fans,” Sociology 40, no. 2 (2006), 219‑235.

However, the Paste article is not isolated. For several years, Generation Z — that is, people born between 1997 and 2010 — has raised many questions within the music industry. The advent of this new group of consumers has led to a significant output of market research, press articles and opinions. Their consumer behaviour is regularly presented as breaking with those of previous generations, opening the way for vast speculation as to the consequences of this transformation on the music industry. The live music industry is no exception to this movement. Furthermore, these questions are more broadly part of a period of uncertainty linked to, on the one hand, the return of audiences after health restrictions were lifted and, on the other, the development of new technology, such as live streaming and the metaverse, which promise to redefine the concert experience.

It is in this context that several industry professionals raised certain questions to the CNM and that the idea for this article emerged. Its aim is to unfold the challenges of the relationship between Gen Z and live music in order to propose an initial examination. It is by no means a complete study on the relationship of 13–26-year-olds to music, or even to live music. However, the aim is to compile existing knowledge on the subject and to open a reflection not only from a research perspective, but also from a professional and political perspective too. To do this, this article brings together three types of materials. To begin with, it relies on various secondary sources (academic literature, reports, official statistics), even if this topic has been little studied. Following this, the CNM organised two workshops with a total of thirteen participants from the industry,4The two workshops took place in autumn 2022. They lasted three and four hours respectively. Participants were selected through CNM’s network. We were mindful to ensure a diverse representation of different organisations according to their geographic location and activity (festivals, concert venues, booking agents). which brought to the fore the issues and personal experiences that have fed this text. As such, this article focuses as much on the consumer behaviour of 13–26-year-olds as it does on the relationship that the live music industry has with this age group, the way the industry apprehends this group and the questions this raises. Finally, the CNM conducted twelve exploratory interviews with people between the ages of 13 and 25.5The twelve interviews were conducted by Robin Charbonnier and Jade Brunet from the Centre national de la musique in December 2022. Each lasted between eighteen to forty-six minutes and focused on the interviewees’ practices and consumer behavior. Interviewees were recruited via the interviewers’ personal networks, taking care to ensure a diverse representation of interviewee profiles. At the time of the interview, the interviewees were aged between thirteen and twenty-five. Two lived in Paris, six in the Île-de-France region, and four from elsewhere in France. Four stated that they attend more than ten concerts a year, three say three to five, and five say one or none. These original empirical elements made it possible to further enrich the content of the reflection proposed here.

This shortwave is split into three sections. The first focuses on the practices and consumer behaviour of 13–26-year-olds. The second section focuses on the relationship between concerts and online media spaces. The third section considers three challenges to question the mutual relationship between the live sector and young audiences. The conclusion outlines some avenues for further reflection.

Who are Gen Z?

The term Gen Z (for Generation Z) is primarily used in marketing literature.6See for example, Henrik Bresman and Vinika D. Rao, “A Survey of 19 Countries Shows How Generations X, Y, and Z Are — and Aren’t — Different,” Harvard Business Review, 2017-08-25, https://hbr.org/2017/08/a-survey-of-19-countries-shows-how-generations-x-y-and-z-are-and-arent-different. It refers to people born between 1997 and 2010, i.e. aged 13 to 26 in 2023. This generation comes after millennials (Generation Y, people born between 1986 and 1996) and precedes the Generation Alpha (individuals born in or after 2011). However, there is much debate on what constitutes a generation, especially from the point of view of music listening practices.7Hervé Glevarec et al., “Tastes of Our Time: Analysing Age Cohort Effects in the Contemporary Distribution of Music Tastes,” Cultural Trends 29, no. 3 (2020): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09548963.2020.1773247. This is why the use here of the concept “Generation Z” remains delicate. In particular, it is about making the distinction between what is due to an age effect or a generation effect.8The age effect refers to the idea of a particular moment over the course of one’s life (e.g. adolescence or entering adulthood). The generation effect refers to an effect specific to a cohort of individuals and their inclusion in a particular historical moment.

Gen Z: the first post-internet generation?

From a generational point of view, people born between 1997 and 2010 have in common a relationship to music that could be described as “post-internet”, i.e. for them, YouTube, streaming platforms and autotune are not transformations, but just the way it is. Ewa Mazierska, Les Gillon and Tony Rigg state that: “terms such as ‘post-digital’ and ‘post-internet’ do not refer to the period when digital technologies or the internet ceased to operate or matter but, on the contrary, when they became ubiquitous.”9Ewa Mazierska et al., Popular Music in the Post-Digital Age: Politics, Economy, Culture and Technology (New York: Bloomsbury 2018), 3. This “post-internet” characteristic translates paradigmatically as the smartphone, which for many is the main vehicle for listening to music.10Raphaël Nowak, Consuming Music in the Digital Age: Technologies, Roles and Everyday Life (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2016); Sophie Maisonneuve, “L’économie de la découverte musicale à l’ère numérique,” Reseaux 213, no. 1 (2019): 49‑81.

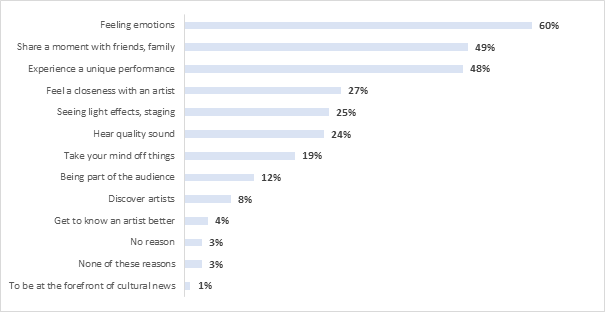

The end of the dominance of the CD as the main format conditioning music duration, what Antoine Hennion calls “discomorphosis,”11Antoine Hennion, Les Professionnels du disque: Une sociologie des variétés (Paris: Métailié, 1981). has led not only to a profound restructuring of the music industries and their value chains,12Jacob Thomas Matthews and Lucien Perticoz, L’Industrie musicale à l’aube du XXIe siècle (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2012); Jim Rogers, The Death and Life of the Music Industry in the Digital Age (London: Bloomsbury, 2013); David Arditi, iTake-Over: The Recording Industry in the Digital Era (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014); Maria Eriksson et al., Spotify Teardown: Inside the Black Box of Streaming Music (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019). but also of channels through which music content circulates.13Eric Harvey, “Collective Anticipation: The Contested Circulation of an Album Leak,” Convergence 19, no. 1 (2013): 77‑94; François Ribac, “Amateurs et professionnels, gratuité et profits aux premiers temps du Web 2.0: L’exemple de la blogosphère musicale,” Transposition, no 7 (2018): https://journals.openedition.org/transposition/2483; Maria Eriksson, “The Editorial Playlist as Container Technology: On Spotify and the Logistical Role of Digital Music Packages,” Journal of Cultural Economy 13, no. 4 (2020), 415‑427; Guillaume Heuguet, YouTube et les métamorphoses de la musique (Bry-sur-Marne: INA, coll. Études et controverses, 2021).As such, the arrival of a new generation of music consumers is contributing to question the place of concerts in the post-internet landscape. Do 13–26-year-olds have different expectations? When it comes to the concert experience, what counts for this age group? Unfortunately, there is still a lack of empirical evidence to truly answer these questions. At most, the Pass Culture study on young people’s view of live music provides some initial explanations.14Concerts et festivals: Quel regard les jeunes posent sur la musique live?, Pass Culture and Prodiss (2022): https://smallpdf.com/fr/file#s=275633fd-23e7-4343-b110-621c688d9ad6. Without any real reliable reference points, the expectations identified are very similar to the arguments usually put forward to qualify the value of the concert experience:15Antoine Hennion, “Scène rock, concert classique,” Vibrations Hors-série (1991): 101‑119; Philip Auslander, Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture (London: Routledge, 2008); Laure Ferrand, “Comprendre les effervescences musicales. L’exemple des concerts de rock,” Sociétés 104, no. 2 (2009): 27‑37; Yngvar Kjus, Live and Recorded: Music Experience in the Digital Millennium (Berlin: Springer, 2018); Fabian Holt, Everyone Loves Live Music: A Theory of Performance Institutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020); Loïc Riom, “Faire compter la musique. Comment recomposer le live à travers le numérique (Sofar Sounds 2017-2020)” (PhD thesis, CSI Mines-Paris PSL, 2021). co-presence, the unique and fleeting nature of the moment, the sound quality. The interviews conducted by the CNM agree with this observation: the information given by the interviewees does not seem that much different from the information given by older generations.

Figure 1: Expectations concerning concerts and festivals, compared to music consumption at home (source: Pass Culture study, Concerts et festivals: Quel regard les jeunes posent sur la musique live?)

Age of first concert

Age-wise, Gen Z are at a pivotal point in their journey as music fans. The interviews conducted by CNM reflect here what has been suggested by other studies:16Antoine Hennion et al., Figures de l’amateur: Formes, objets, pratiques de l’amour de la musique aujourd’hui (Paris: La Documentation française, 2000); François Ribac, “L’apprentissage des musiques populaires, une approche comparatiste de la construction des genres,” in Sylvie Ayral and Yves Raibaud, eds., Pour en finir avec la fabrique des garçons. Vol. 2: Sport, loisirs, culture (Pessac: Maison des Sciences de l’Homme d’Aquitaine, 2014); Sylvain Martet, “Découverte et partage des goûts musicaux: Une analyse des parcours d’auditeurs de jeunes adultes montréalais” (PhD thesis, Université du Québec à Montréal, 2017). it is often during this period — somewhere between the end of adolescence and the beginning of adulthood — that people go to their first concerts in a peer group without their parents and establish their concert-going habits. For example, Marguerite17Names have been replaced with pseudonyms. (19 years old in 2022) explains that after attending many concerts with her parents, she went to her first “real” concert at a festival with her friends and lied to her parents about what she was doing. For many, these first experiences mark the discovery of a new aspect of what a pop concert is. While some have already been to concerts with their parents, both the type of music and the modalities of the experience (for example, experiencing the show from the mosh pit rather than staying in the stands) are often not the same. Aurore (16 years old in 2022) remembers being fascinated by crowd movements, especially when the audience starts a Mexican wave. She also found it amusing at being able to watch the concert on the screens on either side of the stage like she could at home. This kind of account of amazement and enthusiasm is shared by many of the interviewees.

However, there is no standard way for this transition to occur.18Maarit Kinnunen et al., “Live Music Consumption of the Adolescents of Generation Z,” Etnomusikologian vuosikirja 34, (2022): 65‑92. For some, concertgoing is centred around seeing a few select artists for which they claim to be fans. For example, Marie (16 years old in 2022) talks about her first experiences of K-Pop concerts. She insists on her special relationship with the artist, which is expressed notably through specific merchandise just for fans.19Elena Nesti, “‘I Look at Her and I Dance’: Fans Seeking Support in the Movement of a Performing Body,” Ateliers d’anthropologie 50 (2021): https ://journals.openedition.org/ateliers/14876. For example, fans of the Korean group BTS are invited to come to the group’s concerts equipped with an army bomb, a kind of light stick specially designed for the band. “You go to a concert if you know the artist and to sing the lyrics,” she adds. Others mention that they are drawn to the concert experience itself and the connection made with the artists. This is the case of Clara (23 years old in 2022) who conscientiously lists in an Excel table all the concerts she has been to. She explains that the concerts she attends are “more representative” of her music tastes than what she listens to on Spotify. Meanwhile, at the other end of the scale, some interviewees rarely go to concerts, and the rare occasion they do go is because they are following their peers. Take Kingsley (25 years old in 2022), who remembers that his brother “motivated” him to go to a festival because there was “not much else to do.” Finally, a handful are directly involved in organising concerts. Marguerite (19 years old in 2022) explains: “I don’t go to many concerts because I don’t have much money.” However, she volunteers at an association which organises a festival as well as concerts. She explains that she goes to concerts not only based on the music genre, but also for reasons related to activism.

If these accounts highlight the diversity of modalities for first concert experiences, they also underline that these modalities are not detached from their social background. In this respect, the POLE study shows that in the Pays de la Loire region in France, 41% of children from working-class and agricultural families never go to concerts, whereas this rate is only 15% among children from white-collar families.20Claire Hannecart et al., Rapports des jeunes à la musique à l’ère numérique. Synthèse de l’enquête menée en Pays de la Loire, Le POLE (2015). The results also describe significant differences in terms of concert-going practices and music consumption: venues frequented, musical genres listened to, etc.

This brief overview highlights the differences in the relationship of 13–26-year-olds to concerts, not only with regard to how they consume music and the venues they frequent, but also to the tools, devices and mediations through which their habits are established.21On the notion of médiation, see Antoine Hennion, La Passion musicale. Une sociologie de la médiation (Paris: Métailié, 1993). In short, while there may be a temptation to standardise this generation, it is necessary to keep in mind the heterogeneity of practices and relationships to concerts. Seen from this angle, issues related to, for example, gender, age and social background should not be overlooked.

Concerts accessible to all: the end of a “young-people’s practice”

So far, we have reviewed certain elements that appear to characterise the habits of Gen Z. However, the live music industry has also changed a great deal over the past fifty years.22Gérôme Guibert and Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux, Musiques actuelles: Ça part en live (Paris: IRMA, 2013); Simon Frith et al., The History of Live Music in Britain, Volume 3, 1985-2015: From Live Aid to Live Nation (London: Routledge, 2021); Steve Waksman, Live Music in America: A History from Jenny Lind to Beyoncé (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022). It has experienced a new economic boom,23Guibert and Sagot-Duvauroux, Musiques actuelles; Fabian Holt, “The Economy of Live Music in the Digital Age,” European Journal of Cultural Studies 13, no. 2 (2010): 243‑261; Holt, Everyone Loves Live Music. even though for a long time the music industry had considered it to be a peripheral activity deemed hardly profitable.24Simon Frith, “La musique live, ça compte… ,” Réseaux 141‑142, nos. 2 and 3 (2007): 179‑201 Both in France and internationally, the number of music shows has increased sharply. In France, the number of contemporary music shows have increased from 44,860 in 2010 to 73,056 in 2017.25La Diffusion des spectacles de musiques actuelles et de variétés en France, Centre national de la musique (2022): https ://cnm.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/CNM_CDLD_22_MaMA.pdf.

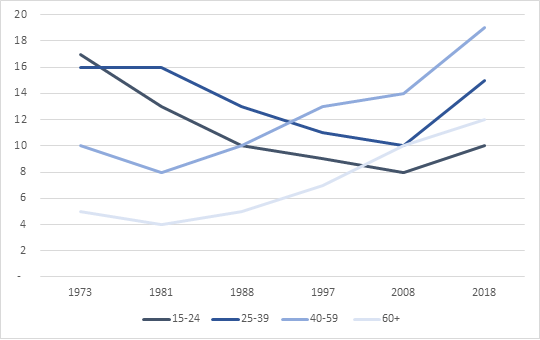

With concerts becoming accessible to the masses, this trend is accompanied by what the French Ministry of Culture describes as a “condensing of practices.”26 Philippe Lombardo and Loup Wolff, “Cinquante ans de pratiques culturelles en France,” Culture études 2, no. 2 (2020): 50. In 1997, 29% of the French population said they had gone to a concert in the last twelve months compared to 34% in 2018.27Presentation of the DEPS survey as part of the French Ministry of Culture’s symposium “Colloque ‘40 ans de fêtes de la Musique,’” YouTube, 2022-06-16: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A45RmTljHkQ. Those under the age of 26 are therefore beginning their concert-going practices at a time when it is becoming more and more widespread. Furthermore, as the graph below shows, while going to pop concerts was considered as a “young people’s practice” in the 1970s and 1980s, this is no longer the case at all. The figures from the French Ministry of Culture attest to a convergence of practices between age groups. “Contrasting, sometimes divergent depending on the type of show, the changes observed concerning the whole live entertainment industry are reflected overall by a significant reduction in the differences between practices that prevailed until then, in particular in terms of age and hometown.”28Philippe Lombardo and Loup Wolff, “Cinquante ans de pratiques culturelles en France,” 59. These figures even suggest a decline in pop concert attendance since the 1970s in the 15-24 age group (see graph below).29his drop is even greater for the “rock or jazz” category. However, it remains difficult to assess whether this is not an effect of genre classification and in particular the absence of a ”rap” answer option. For all concert types, the available figures indicate that for the 15-24 age group concert attendance over the course of a year has fallen from 40% in 1997 to 37% in 2018.

Figure 2: Evolution by age of concert attendance for national and international pop artists, 1973-2018 (% having attended a concert for a national or international pop artist over the course of a year) (Source: Enquête sur les pratiques culturelles, 1973- 2018, DEPS, French Ministry of Culture, 2020)

Other reports worry about a possible drop in attendance by younger people. The Baromètre des pratiques culturelles des Français en matière de spectacles musicaux et de variété indicates that while young people (under 35 years old) go to concerts more than the average French person, 44% of respondents in the 15-24-year-old category say they are thinking about cutting back their attendance.30Baromètre des pratiques culturelles des Français en matière de spectacles musicaux et de variété, Prodiss and Observatoire du live (2022). The main reasons given to justify this stance (all age groups combined) were financial concerns (48%), lack of motivation to go out (30%), concerns surrounding Covid-19 (22%) or choosing to devote time to other activities (19%).

Several participants in the two workshops shared in part this observation, relaying a concern about young people’s concert attendance and lamenting their venue’s aging public. One industry professional rightly points out, “We are losing our young people.” This somewhat paradoxical situation brings them closer to the problems encountered for many years by classical music institutions concerning attracting new audiences.31Pierre-Michel Menger, “L’oreille spéculative. Consommation et perception de la musique contemporaine,” Revue française de sociologie 27, no. 3 (1986): 445‑479; Stéphane Dorin, Déchiffrer les publics de la musique classique. Perspectives comparatives, historiques et sociologiques (Paris: Archives contemporaines, 2018).

However, it remains difficult to draw definitive conclusions from these figures. On the one hand, the drop illustrated remains weak. On the other, the share of the concert-going population remains largely in the minority (barely a third of those over age 15, see above). This is even more so for those who attend concerts regularly. The figures from the POLE study show that young people who go to more than three concerts a year represent only 14% of those surveyed.32Hannecart, Rapports des jeunes à la musique à l’ère numérique.From this point of view, population-based studies have major limitations in accurately reporting on concert attendance dynamics, which are more relevant to regular concert-goers. Moreover, both the interviews conducted by the CNM and the qualitative research that has taken an interest — sometimes in a somewhat indirect way — in these issues33See for example Loïc Riom, “Faire compter la musique. Comment recomposer le live à travers le numérique (Sofar Sounds 2017-2020)”; Sophie Turbé, “Observation de trois scènes locales de musique métal en France: Pratiques amateurs, réseaux et territoire,” (PhD thesis, Université de Lorraine, 2017); Michael Spanu, “Pratiques et représentations des langues chantées dans les musiques populaires en France: Une approche par trois enquêtes autour du français, de l’anglais et de l’occitan,” (PhD thesis, Université de Lorraine, 2017); Kjus, Live and Recorded; Holt, Everyone Loves Live Music; Ben Green, Peak Music Expériences: A New Perspective on Popular Music, Identity and Scenes (London: Routledge, 2022). do not in any way suggest a strong disaffection for concerts amongst 13–26-year-olds.

That said, the results of these studies underline that at least three major transformations which have affected the live music sector since the turn of the 2000s are reflected in 13–26-year-olds’ introduction to concert-going practices. First, festivals are becoming increasingly important and their number has increased considerably.34Edwidge Millery and her colleagues estimate that almost half of the festivals have been created in the last decade. Edwige Millert et al., “Cartographie nationale des festivals: entre l’éphémère et le permanent, une dynamique culturelle territoriale,” Culture études 2, no. 2 (2023): 1‑32. These events now largely dictate the structure of touring seasons, especially for international artists.35Emmanuel Négrier et al., Les Publics des festivals (Paris: Michel de Maule, 2010); Andy Bennett et al., The Festivalization of Culture (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2015). In the same way, large arenas such as the Zenith arenas occupy a major place in establishing concert-going habits. The Baromètre des pratiques culturelles des Français en matière de spectacles musicaux et de variét agrees with this.36Baromètre des pratiques culturelles des Français en matière de spectacles musicaux et de variété. It shows that 15–24-year-olds prefer large venues to small ones. This trend can also be seen in the figures from the POLE study.37Hannecart, Rapports des jeunes à la musique à l’ère numérique. This type of venue is recent and partly responds to the transformations in the live sector mentioned above.38Robert Kronenburg, This Must Be the Place: An Architectural History of Popular Music Performance Venues (New York: Bloomsbury, 2019). For example, while the Zénith arenas in Paris and Montpellier were built in 1984 and 1986 respectively, the other Zenith arenas were built during the 1990s and 2000s. Secondly, the live music sector is experiencing a strong phenomenon of market concentration39 In France, journalistic work has shown that both the main concert venues and the most important festivals are controlled by a few large international groups: https ://www.vousnetespaslaparhasard.com/. See also: Fabian Holt, Everyone Loves Live Music. and globalisation. As such, a large proportion of the artists cited during the interviews conducted by the CNM are international artists, particularly American and Korean. Finally, many international studies have highlighted the increase in ticket prices, especially for large-capacity concerts.40Adam Behr and M. Cloonan, “Going Spare? Concert Tickets, Touting and Cultural Value,” International Journal of Cultural Policy 26, no. 1 (2018): 95-108; Marie Connolly and Alan Kreuger, “Rockonomics: The Economics of Popular Music,” Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture 1 (2006): 667‑719. This increase has an impact on 13–26-year-olds’ concert-going practices. For example, Ariane (16 years old in 2022) explains how she was unsure about going to see Orelsan in concert, which she viewed as an “investment.” She explained that she was stressed about spending so much money and the risk of getting bored. During the workshops, several industry professionals showed awareness of the issues related to price inflation.

Following this initial overview, the rest of this article is structured in two parts. The next section explores in more depth the relationship of 13–26-year-olds to concerts according to their internet and social media use. The third section will aim to outline avenues for further reflection.

Bringing the live music industry to the internet (and vice versa)

The relationship between the internet and the live music industry is not an obvious one. While young people are mainly using streaming platforms and social media to listen to music,41The Enquête sur les pratiques culturelles 2018 shows that 90% of 15–24-year-olds listen to music on digital media (digital files, online services). See DEPS, Chiffres clés 2022, French Ministry of Culture, 2022. MIDiA reports that in the UK, 53% of 16–19-year-olds use Spotify on a daily basis. Broadly speaking, studies also agree on the fact that under 26s pay to access a streaming package. Nevertheless, if streaming listening is widely used in this age group, other practices are observed. Still according to DEPS figures, 24% of 15–24-year-olds listen to music on physical media (CDs, cassettes, vinyl). On this topic, see also Raphaël Nowak, Consuming Music in the Digital Age; Quentin Guilliotte, “La persistance de l’attachement aux biens culturels physiques,” Biens symboliques 9 (2021): https://journals.openedition.org/bssg/864; Baromètre de la consommation de biens culturels dématérialisés, Hadopi, 2021. one might wonder, on the one hand, about the place of live music in digital spaces and, on the other, about how these devices enhance, prolong or inhibit the live musical experiences. These questions were raised during discussions with industry professionals and appear to be a major challenge. It concerns how festivals and concert venues are marketed, as well as their online presence.

Music listening in 2022 is a connected practice

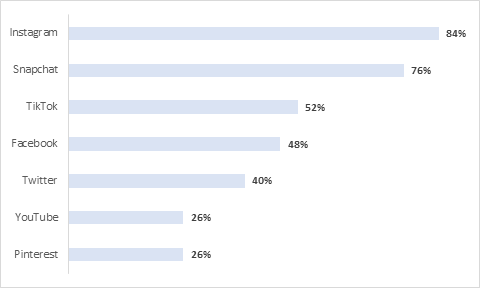

All of the reports on Gen Z consumer behaviour insist on the importance of social media in their music listening practices. Their use of social media is not only very significant, but above all regular.42For example, for the UK see Mark Mulligan, Gen Z. Meet The Young Millennials, MiDiA, 2017. For the US see Ana Dartaru, “What Clicks with Gen Z,” Creatopy, 2022-07-22: https://www.creatopy.com/blog/whitepaper-what-clicks-with-gen-z/. In France, a 2022 survey showed that the most used social media in 2021 were Instagram (84%) and Snapchat (76%), followed by TikTok (52%), Facebook and Twitter (see below).43Mehdi Bautier, “Réseaux sociaux: les 16-25 ans abandonnent Facebook pour TikTok,” Diplomeo, 2022-02-03: https://diplomeo.com/actualite-sondage_reseaux_sociaux_jeunes_2022?utm_source=blogdumoderateur&utm_medium=siteweb&utm_campaign=etude-usage-reseaux-sociaux-generation-z-2022&utm_content=lien&utm_term=Diplomeo. The same study shows strong changes in social media use. For example, Facebook usage went from 93% in 2017 to 48% in 2021 amongst those surveyed, unlike TikTok which did not exist in 2017 but which is now in third position in the ranking.

Figure 3: The most popular social media platforms in France in 2021 (source: Diplomeo)

The interviews conducted by the CNM mention profusely the use of social media in connection with music in general, and particularly with concerts. From sharing a gig announcement with friends to buying tickets, arranging to meet one other, getting directions to the venue, showing your ticket to enter the venue, and taking a photo of the artist on stage, it seems unimaginable today to go to a concert without a smartphone.44We can also note that we still know little about the proliferation of apps that aim to accompany the concert experience: setlist sharing, online ticketing, recommendations, etc. For example, Nikolas (20 years old in 2022) explains that when he goes to a concert, when he’s waiting in the queue he scrolls through the artist’s stories, as well as those of artists who may be in attendance or even the concert venue’s stories. In this way, he hopes to have access behind the scenes or to find out if the artist announces special guests. During the concert, he also often makes a story to show that he is at the concert “and to save the memory.” This does not prevent him from interacting with other people around him.

Not only does social media go hand in hand with concerts, it is also used to prepare for a concert too. Clara (23 years old in 2022) says that at the start of Californian musician Steve Lacy’s tour, the public only knew “his most famous TikTok” (i.e. an extract from one of his songs ). She explains that this annoyed the artist a lot, making it known on social media, and provoked a reaction from his fans. When she saw him in concert at the Trianon, the public knew all the lyrics to the songs. This example captures the complexity of the relationship between online listening and what happens during concerts. Above all, it underlines that one does not replace the other, but that the challenge is indeed the way in which devices and consumer behaviour fit together. On the other hand, what emerged from these interviews is that a concert is rarely the first interaction a person has with an artist.

The interviews conducted by the CNM clearly show that smartphones and social media have become essential “prostheses”45Nicolas Nova, Smartphones (Geneva: Métis presses, 2020). at concerts. These new devices inform, guide, dictate, and document. They also enable new forms for experiencing live music to be imagined, for which young people are rightly or wrongly considered early adopters.

New formats, augmented concerts?

The lockdowns implemented following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic gave rise to an important phase of experimentation and brought to the forefront various technology solutions offering concert experiences, such as live streaming, virtual reality and augmented reality.46Frédéric Trottier-Pistien, “‘C’est ça le futur des soirées?’ Les musiques électroniques de danse à l’épreuve du livestream et de la COVID-19,” Communiquer, no. 35 (2022): 81‑99; Romain Bigay, “Ce que le livestream fait au live,” Communiquer, no. 35 (2022): 25‑37; Gérôme Guibert and Martin Lussier, “La musique live en contexte numérique. Captation, diffusion, valorisation, usages,” Communiquer, no. 35 (2022): 1‑6; Ariane D’Hoop and Jeannette Pols, “‘The Game is On!’ Eventness at a Distance at a Livestream Concert during Lockdown,” Ethnography (2022): https://doi.org/10.1177/14661381221124502; Gérôme Guibert, “Live Performance and Filmed Concerts: Remarks on Music Production and Livestreaming Before, During, and After the Public Health Crisis,” Ethnomusicology Review 24 (2023): https://ethnomusicologyreview.ucla.edu/journal/volume/24/piece/1099. Different studies show a certain appetite amongst Gen Z for these new formats. According to the Étude prospective sur le marché du livestream musical en France,47Étude prospective sur le marché du livestream musical en France, Arcom and CNM, 2022. a prospective study on the music livestreaming market in France, young people are bigger livestreaming consumers than the majority of French people (see below). In the same way, the study Les Français et les spectacles vivants48Les Français et les spectacles vivants, Prodiss, 2022. shows that young people are more tempted by a concert experience in the metaverse (50%) or in augmented reality (52%). However, it should be noted that more often than not, this experience is not in conflict with physical concert attendance. On the contrary, this kind of practice is popular amongst individuals who are regular concert-goers. Rather, they seem to complement the concert experience, if not prolong it.

Figure 4: Profiles of internet users, physical concert-goers and consumers of livestreamed music (Significant differences with internet user profiles highlighted in red and green) (source : Arcom-CNM)

On this point, it is interesting to note that the last few years have seen an increase in recorded formats and a form of blurring the boundaries between live music and recorded music:49For an overview, see Loïc Riom and Michael Spanu,“Les nouvelles médiations audiovisuelles de la musique live: Formats, industrie et patrimoine culturel numérique,” SociologieS, to be published. live sessions available online (NPR Tiny Desk, Colors, KEXP, Sofar, Blogothèque), concerts in virtual worlds (Fortnite and Roblox), or livestreaming platforms.50On these developments in South Korea, see H. Won, “La possibilité d’un nouveau modèle économique avec les concerts en ligne: Un regard socio-économique sur la K-Pop en Corée du Sud,” SociologieS, to be published. Conversely, festivals and concert venues actively use audio and video streaming in their communications, creating new links between these two music listening formats.51Anne Danielson and Yngvar Kjus, “The Mediated Festival: Live Music as Trigger of Streaming and Social Media Engagement,” Convergence 25, no. 4 (2019): 714‑734. In the interviews conducted by the CNM, these new formats appear more like added extras. For example, Clara (23 years old in 2022) regularly watches content published by the webzine Grunt, while Nikolas (20 years old in 2022) watches content published by the online media Brut. However, both Clara and Nikolas are regular concert-goers. The advantage of this type of format being free is emphasised. For example, Kingsley (25 years old in 2022) watched pre-recorded footage of Travis Scott’s concert on Fortnite. He found this concert impressive and spectacular: “It was really him, his music.” He was the only person interviewed to admit that this type of format enables him not to go to concerts, for which he is not that much interested in doing. For others, concert recordings or online concerts reflect an artist’s performance and can convince them to buy a ticket they deem too expensive (see above).

For some industry professionals and their colleagues, concert live streams or recordings are seen as a means of reaching young people. Many noted that YouTube is experiencing a renewed resurgence and were surprised by the number of views of certain content posted online. Incidentally, these views are not necessarily live and replays sometimes generate “remarkable” viewing figures, which surprised several participants in the workshops. “We are quite surprised to see that the content exists without the experience of the given moment,” remarked one participant.

Concerts do indeed find a place in online media space. However, the encounter between these two spaces — the concert in the venue or the festival and the multiple parallel existences on social media — is not easy to achieve.

A media space which concert venues and festivals struggle to get to grips with

The twelve young people interviewed by the CNM use social media extensively — with Instagram and TikTok ahead — for keeping up to date with music news. Meanwhile, industry professionals expressed their difficulty in making themselves visible on these media spaces. First of all, communicating on social networks requires significant resources. Teams do not always have sufficient human resources to take on this task. The difficulty is accentuated by the fact that each social network has its own posting logic and very often requires specific content to obtain a good “reach.” So, if several concert venues and festivals communicate regularly on Facebook and Instagram, they would need to rethink their strategy if they were to target Snapchat or TikTok. These two platforms offer, above all, video content that requires suitably adapted communications strategy. One festival communications manager explains: “Snapchat, we’re not into it because it’s used for talking into the camera and sharing moments with friends. So there is little interest in our presence here. Rather, we try to create moments in the festival that our festival-goers will want to share and be our representatives influencing on this platform.”

If producing promotional digital content (bannering, stories, etc.) remains within reach, the most popular content on these networks — such as interviews in front of the camera — is more complex to produce. The artist and staff need to be available before the concert, and media-specific skills are required for each platform. In the workshops, some people also wondered if this task should really fall to live music professionals. Finally, everyone pointed out that having a social media presence requires you to post regularly if you want a chance at gaining visibility.

This increase in formats presents a second difficulty. On this topic, many pointed out that these platforms evolve rapidly, requiring them to monitor uses and regularly renew communication strategies. One participant in the workshops said: “Five years ago, we had social media training, and it was focused on Twitter. Today it’s all about TikTok.” Industry players are struggling to keep up with these changes. They find themselves making costly transfers of their community from one (declining) network to another (growing) one. Furthermore, older community managers are now experienced on Facebook, but lag behind on the new networks. Venues and festivals admit to focusing on creating experiences that can be shared on social media — “Instagrammable” — or try to bring in Youtubers to bring the venue to life, and to delegate social media content creation and distribution to artists or the public themselves.

The third issue goes beyond the challenge of communicating between concert producers and concerns all media players in the music industry (press, blogs, newspapers). The industry professionals who participated in the workshops revealed that they partly share the difficulties they encounter. In fact, when it comes to these new social media platforms, concert producers cannot rely on the people with whom they usually work. They are having to learn how to collaborate with new “influencers” and trend-setters. The workshops revealed that there is a real lack on this level. More broadly, the values that are defended on social media platforms sometimes go against those defended by certain participants and their venues. The short formats of these platforms also raise questions about how they shape musical content production and distribution, as in the example reported above by Clara.52In Art Worlds, Howard Becker already mentioned this complicated relationship between musical production and the time available to musicians on recording media. Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds (Berkely and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982). As such, they lack an alternative which offers a means of communication consistent with their image. Conversely, it is not always so easy for Internet stars to adapt to the concert format. Amongst the young people interviewed by the CNM, Pearl (13 years old in 2022) explains that she listens to music by Youtubers, but that if she were to go to one of their concerts, it would be more because she would want to see them than because she really likes their music. Incidentally, several Youtubers have attempted tours without achieving the success expected.53On how YouTube is used by artists, see in particular Caroline Creton, “Approche communicationnelle des scènes musicales locales face à l’offre médiatique numérique: le cas nantais” (PhD thesis, Université de Rennes 2, 2019); Caroline Creton, “L’image au cœur des pratiques communicationnelles des scènes musicales,” Revue française des sciences de l’information et de la communication, no. 18 (2019): https://journals.openedition.org/rfsic/8262#quotation.

The challenge lies in knowing how to build presence for concert venues on social media. As such, one might wonder if there is not a form of compartmentalisation between certain venues and the media spaces frequented by 13–26-year-olds. In some cases, it is striking to note that it is above all the artist who is the communication channel towards what becomes their audience.54Brian Hracs et al., “Standing out in the Crowd: The Rise of Exclusivity-Based Strategies to Compete in the Contemporary Marketplace for Music and Fashion,” Environment and Planning A 45, no. 5 (2013): 1144‑61; Nancy K. Baym, Playing to the Crowd: Musicians, Audiences, and the Intimate Work of Connection (New York: NYU Press, 2018); Loïc Riom, “Discovering Music at Sofar Sounds: Surprise, Attachment, and the Fan–Artist Relationship” in Tamas Tofalvy and Emília Barna, eds., Popular Music, Technology, and the Changing Media Ecosystem (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020): 201‑216. The interviews conducted by the CNM reinforce the observation made by those in the industry: it is quite rare for young people to be attached to a certain venue. Above all, what counts for them in concert attendance is the name of the artist.55In 1991, Antoine Hennion noted these different mediations which create the artist-audience relationship: “These asymptotic set-ups are performative patterns, efforts to ‘produce’ music, by defining in passing, in the strongest sense of the term passage, its subjects, objects and means.” Antoine Hennion, “Scène rock, concert Classique.” From this point of view, “young” audiences pose a problem for those in the sector: in what other ways can they reach this audience? The last section of this article offers some avenues for reflexion on this topic.

How to bring concerts to Gen Z?

So far, this article has tried to provide an overview of the current situation. We have seen how social media, the internet and the practices that accompany them disrupt and reinvent the relationships between concerts and their audiences. This last section aims to outline some of the challenges facing players in the sector, starting from a relatively simple question: how to bring concerts to Gen Z?56Here I adopt a formulation of Antoine Hennion for examining music theory lessons. Antoine Hennion, Comment la musique vient aux enfants. Une anthropologie de l’enseignement musical (Paris : Anthropos, 1988). Or rather, what we’re interested in is why wouldn’t concerts not or no longer be brought to them? By questioning concert “publicity,” that is to say all the channels that bring an audience into a venue,57Loïc Riom, “Mettre la musique en public: quelques réflexions à partir d’une ethnographie des soirées de Sofar Sounds” in Anthonu Rescigno et al., eds., Le Public dans tous ses états (Nancy: Presses universitaires de Nancy, 2022). this section examines three issues that deserve to be tackled head on in order to imagine new generations’ relationship with concert venues and festivals: Gen Z’s tastes; the reasons for possibly feeling removed from concert venues and festivals; and how this generation are getting involved with concerts and festivals. Without going into a form of scaremongering, the gamble here is to explore in depth the hypothesis — a hypothesis that’s still difficult to verify from the data we have — of young people’s (or indeed some young people’s) potential disinterest in concerts. Each of these three issues suggests potential discrepancies and can help to understand why concerts would not, or no longer, be brought to young people.

Gen Z’s tastes: influencing in motion

Young people’s music tastes provoke much speculation between predicting the return of rock music or, on the contrary, affirmation of the unassailable hegemony of urban music. This question is nevertheless interesting, because it allows us to come back to the influential role of concert venues. Indeed, to influence, it is not simply about giving an order, you must also be engaged in the effort, accompany the recommendation, adjust it depending on what is recommended and to whom it is recommended.58Pierre Delcambre, “Prescrire comme opération sociale,” Territoires contemporains, no. 11 (2019): http://tristan.u-bourgogne.fr/CGC/publications/prescription-culturelle-question/Pierre-Delcambre.html; Jedediah Sklower, Le Gouvernement des sens. Militantisme jeune communiste, médias et musiques populaires en France (1955-1981) (PhD thesis, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2020). All venues and festivals would like to be able to satisfy directly Gen Z’s tastes. However, those who participated in the workshops rightly point out the difficulty of the task: what music genre brings in young audiences? You have to “stay in the know,” “be ahead of the curve,” as the director of a venue specialising in rap explains.

According to these same industry professionals, the paradox is that it is not the music that they are in to. This issue is much trickier since, as we have seen, the media landscape surrounding concert venues has changed considerably. From this angle, rap and urban music are a point of tension. These music genres maintain a form of distance vis-à-vis part of the sector, even if this point tends to change. In fact, despite “urban music” — particularly driven by young people’s music listening behaviour — monopolises the top spots in the streaming charts, the genre remains a minority on concert venue and festival programmes. During the workshops, several people put forward an explanation that it is hard to book an artist who experiences dazzling success and quickly become financially beyond the reach of their venue or festival. From this point of view, having a career in rap music is unsuited to the indie circuit, which gives a prominent place to concerts in the development of an artist’s career.

This lack of understanding seems to extend to organisational issues. Interviewees cite a lack of professionalism and difficulties in working with the artists’ entourages: improvisation, imprudent logistical requests or last-minute cancellations. The interviewees also indicate another way of looking at the concert format for artists “accustomed to thirty-minute sets in a nightclub.” Over the past thirty years, concert venues and festivals have made significant efforts to professionalise, especially to meet government requirements.59Eve Chapello, “Les organisations et le travail artistiques sont-ils contrôlables?” Réseaux 15, no. 86 (1997): 77‑113; Emmanuel Brandl, L’Ambivalence du rock, entre subversion et subvention: Une enquête sur l’institutionnalisation des musiques populaires (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2009). The sector’s structuring seems to hamper the integration of newcomers (especially rap artists and their entourage) who do not (yet?) have this professional culture. Apart from that, what is also at play is a mutual understanding of what constitutes a musical performance and a good concert. For example, the use of a playback track serves to indicate an ultimately limited performance quality given the “disproportionate” means and fees demanded. What seems at stake here is therefore not only the development of new skills to know how to appreciate young people’s “tastes”, but also, perhaps, the possibility of creating a common professional co-existence.60These tensions affect different issues. For example, some rap artists prefer the status of autoentrepreneur (self-employed) to that of intermittent du spectacle (a work status specific to France, whereby those in the live entertainment industry work temporary contracts and are subsidised by the French state in between freelance jobs). Robin Charbonnier, La Régulation à l’épreuve du changement: Le cas de la musique (PhD thesis, École Polytechnique Paris, 2022). In other words, the challenge does not simply come down to dictating that rap or urban music should occupy more space in programming, but indeed to work within the live sector to achieve this integration.

Unable to identify with music programmes

During our discussions with industry professionals, one of them put forward the hypothesis that “young people don’t identify with” what is offered by festivals and concert venues. This phrase resonates a lot with several aspects of the discussions with CNM interviewees. So what’s making young people unable to identify with this space? Identifying with something can, first of all, mean not finding your niche or the music that matters to you. For example, several of the 13–26-year-olds interviewed by the CNM raised the case of international artists whom they like and who ultimately rarely tour in France, and when they do, they play at large Parisian venues and the ticket prices are expensive (see above). Others, like Victor (22 years old in 2022), sit at the other end of the scale, explaining that they will never be able to see their favourite artists because they are no longer alive. Apart from the sole issue of programming rap artists, a concert is dependent on the tour date schedule which is sometimes unaligned with the tastes of those interviewed, such as listening to “back catalogue” music or party-inspired practices. As the director of a concert venue pointed out, rap is perhaps only a drop in the ocean of music genres linked particularly to dancing and for which not many of these types of concerts exist: Afrobeat/coupé-décalé/zouk.

Not identifying with something also means not finding yourself somewhere, not having been there and perhaps also not having been taken there. This meaning reintroduces the notion of the geographical distribution of concerts and the issue of the having local concert venues. The question of accessibility is central, especially in small towns and suburban regions that do not have good public transport networks. In fact, young people do not always have easy access to a vehicle, which limits their opportunity to go out, especially when concert venues are located in suburban areas where it is often expensive to set up shuttle services. This problem is somewhat different for festivals, especially in the summer, as they can provide onsite camping at the event. In the city, organising events “outside the city” and “work on the ground” are used to attract an audience that does not usually travel. Partnerships with local associations and organising community-based events were mentioned on several occasions as means of (re)creating this bond with communities neighbouring venues.

Finally, the notion of identifying with something relates to the concert experience itself. For example, Kingsley (25 years old in 2022) criticises artists for being all about the “fame” and for playing at large venues only “for the money.” For Kingsley, the concert experience is not satisfying: “too many people”, “too expensive”, “too far from the artist.” He prefers to watch audio-visual content on the internet, in particular on YouTube or “Insta Live.” He feels closer to the artists here. He considers that artists are more real on social media than in live concert. Lara (15 years old in 2022) explains that her friends told her about their concert experiences, but she was not interested because she does not like the atmosphere and thinks there are too many people. She believes that Covid-19 may have played into the fact that she avoids going to crowded places. Kingsley and Lara’s accounts suggest a gap with the experience offered by venues and festivals. In the same way, several industry professionals expressed a form of lassitude amongst part of the public, potentially linked to the pandemic. This lassitude, sometimes described as “laziness,” pushes some people to go out less and to choose other forms of cultural consumption (especially online).

Faced with these findings, several industry professionals detailed the various initiatives they are developing to offer formats that meet different expectations: “after school” events with early opening hours, debates, workshops, partnerships with associations. These initiatives raise the question of mediation — or outreach and engaging new audiences — inclusive of all these channels, of these moments that forge links between a concert venue or a festival and its audience. From this point of view, it is undeniable that a number of avenues can still be explored to bring in young people and “use them” to create projects, as one of the people present at the workshops nicely put it. However, as these examples show, building their interest requires rethinking the way concerts are structured and being ready to adapt. As the director of a Parisian venue explained: “We wanted to get closer to the local audience, which is interested in urban music, and the solution was to say to them ‘What do you need?’, rather than ‘Come to the concert!’ That’s what created the link, a bit like a community youth club back in the day.” This reflection perhaps invites us to consider the concert venue differently as a place, less as only a space for welcoming artists on a national or international tour, but also as a point of resonance rooted in its local region.

If what prevents young people from coming to concerts raises questions, the opposite question also deserves to be asked: what place are concert venues ready to make for younger audiences? Do they really want to welcome them? Many of those who took part in the workshops underlined the organisational weight of welcoming young audiences. The types of constraints mentioned include first of all legal ones, such as opening hours and the sale of alcoholic beverages. Young audiences are also described as more hectic and less easy to manage. The organisers mention greater needs for safety or security which increase the cost of producing an event. Finally, some of those who work at venues cite the risk that their venue will be perceived as “too young” alienating and loosing part of its public. These elements remind us that welcoming “young people” is also not obvious from the point of view of industry professionals. To welcome them would require adapting much more than just the programming alone, affecting all stages of concert production.

Making the change

Beyond concert production, discussions with industry professionals highlighted the issue of the place of young people within the venues and festivals themselves. While they realise that young people want to be actors in events on the ground,61On this point, the Pass Culture study states that 43% of respondents would be ready to go beyond the spectator experience and commit to helping organise a concert or festival. Concerts et festivals: Quel regard les jeunes posent sur la musique live ?. this does not necessarily translate into voluntary participation or reappropriating venues for themselves. Several people tell of the limits in mediation actions, for example, in helping organise a concert. If young people participate willingly, this does not guarantee that they will come back on a regular basis. Conversely, several venues have observed that their volunteers are in fact getting older. This could be explained by a loss of political will for organising concerts especially compared to when community youth centres and the first SMACs (scènes de musiques actuelles, a contemporary music network of venues given this status by the French Ministry of Culture) were created.

It could be too rash to conclude that professionalising the sector tends to widen a gap. However, several of the people we spoke to report similar challenges in terms of human resources. Staff turnover issues affect both a venue’s boards of directors and salaried jobs. Other issues highlighted include high demands in terms of working conditions (salaries, working hours, workplace well-being, etc.) in a sector where graduates are often paid less than in other jobs. Furthermore, teams experience a high turnover rate. In particular, there is a recruitment shortage in administration and communications professions. This reinforces the difficulties in finding skilled workers in key positions that require knowledge of social media (see above).

The question of young people’s relationship to concert venues and festivals goes beyond attendance issues alone. It affects the model of many venues and raises the question of their existence. The director of a concert venue summed up the situation as follows: “In the subsidised sector, we are at the end of something.” If, over the past thirty years, this sector has experienced a rise in professionalisation and structuring, this now raises questions about how this model can take on a new form. At a time when the first generations of professionals who have often carried out a form of activism are reaching retirement,62Catherine Dutheil-Pessin and François Ribac, La Fabrique de la programmation culturelle (Paris : La Dispute, 2017). other methods of engagement may have to be imagined.

What next

The purpose of this article is not to reach a definitive assessment. By going through different issues, the objective was more to raise questions and outline avenues for reflection. And the latter are calling out to be appropriated by others. If a hypothetical decoupling between contemporary music concerts and young people is taking place — and I hope I have shown that on this point it is difficult to make a definite assessment — this should enable to open a discussion that goes beyond simplistic explanations that would be tempted to place the responsibility at times on “young people” — whom obsess over their screens — and other times on professionals in the sector — who understand nothing about rap.

However, to carry out this reflection, three topics seem unavoidable. To begin with, as we have seen, there are still too few tools that would allow us to observe changes in contemporary music concert attendance practices. Several surveys have been launched to assess the effects of Covid-19 and health measures, but they often lack a point of comparison. As such, several people during the workshops highlighted the difficulties in carrying out studies on their audiences. While digital “footprints” and data from online ticketing promise new possibilities, many questions in terms of means, legislation and expertise remain unanswered. While this question is becoming a major challenge for the sector,63Gérôme Guibert, “Le tournant numérique du spectacle vivant. Le cas des festivals de musiques actuelles,” Hermès 86, no. 1 (2020): 59‑61. it could enable collaborations between research circles and music industry professionals to develop and strengthen.

Next, reflecting on Gen Z’s relationship with live music also calls for considering what the development of the internet and social media is doing to concerts. This question needs to be asked in the right way to avoid coming up against opposition. On the contrary, digital tools enhance, attract and sometimes prolong the concert experience. Conversely, live music feeds content published online. However, when we paint a portrait of this media landscape, both its dependence on large digital companies and the financial investments required to exist there are obvious.64On livestreaming, see in particular H. Won, “La possibilité d’un nouveau modèle économique avec les concerts en ligne: Un regard socio-économique sur la K-Pop en Corée du Sud.” There is certainly a decisive cultural policy issue here, the importance of which is likely to increase in the years to come. How do you enable independent music media to exist on social media? With what business models? How can other communication channels be offered to actors in the sector? Should public money be used to pay for advertising on social media? How can we protect a form of diversity in the content offered by these platforms? How can we guarantee the existence of a royalty distribution mechanism between the players in this media ecosystem? All of these issues are already being discussed. However, in light of the promises of the metaverse, but also of strong market growth,65Goldman Sachs estimates the live market at $38.3 billion in 2030 compared to $29.1 billion in 2023. Source: Goldman Sachs, Music in the Air, 2022-06-13: https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/gs-research/music-in-the-air/report.pdf. it would undoubtedly be regrettable to think that they do not concern concert production. From this point of view, industry professionals have every interest in getting involved in these questions.

Finally, this topic is dense, in the sense that it affects all the elements that underlie the existence of a concert production structure, whether that’s a venue, a festival and even a booking agent. It’s not just about programming more rap, or subsidising concert tickets for young people. Of course, these elements can be possible answers. However, both the interviews conducted by the CNM and the two workshops organised with industry professionals show that the challenge is to forge a common attachment and to nurture it. From transforming the media landscape to making concerts accessible to all, structuring the sector and even increasing ticket prices, many processes contribute to putting this mutual attachment to the test. As such, a certain model of what a concert venue or an (independent) festival is may need to be reinvented. If during the majority of the history of contemporary music the link between concerts and young people appeared obvious, the fact that it could potentially be in the process of being undone invites us to reflect both on the evolution of 13–26-year-olds’ consumer behaviour and on the transformations in the sector.

Acknowledgements

This text has benefited greatly from the comments of several CNM reviewers, to whom I would like to say thank you. My gratitude also goes to Robin Charbonnier for his support and our always many rich and exciting exchanges. Thanks also to Jade Brunet for her work on the interviews. Finally, I would like to thank both the 13–26-year-olds and the industry professionals who agreed to share their experiences and their questions, thus giving this exploratory reflection some body. The arguments presented here and their shortcomings remain unreservedly attributable to me.

Translated from French by Kate Maidens.

- 1Leila Jordan, “The Kids Aren’t Alright: Inside Gen Z’s Chaotic Introduction to Live Music,” Paste Magazine, 2022-07-14, https://www.pastemagazine.com/music/gen-z-concert-safety/.

- 2For further discussion on this topic, see Agnès Gayraud, Younger Than Yesterday: Jeunesse pop à travers les âges, 2023-01-03, https ://www.theravingage.com/documents/gayraud-younger-than-yesterday.

- 3Andy Bennett, “Punk’s not Dead: The Continuing Significance of Punk Rock for an Older Generation of Fans,” Sociology 40, no. 2 (2006), 219‑235.

- 4The two workshops took place in autumn 2022. They lasted three and four hours respectively. Participants were selected through CNM’s network. We were mindful to ensure a diverse representation of different organisations according to their geographic location and activity (festivals, concert venues, booking agents).

- 5The twelve interviews were conducted by Robin Charbonnier and Jade Brunet from the Centre national de la musique in December 2022. Each lasted between eighteen to forty-six minutes and focused on the interviewees’ practices and consumer behavior. Interviewees were recruited via the interviewers’ personal networks, taking care to ensure a diverse representation of interviewee profiles. At the time of the interview, the interviewees were aged between thirteen and twenty-five. Two lived in Paris, six in the Île-de-France region, and four from elsewhere in France. Four stated that they attend more than ten concerts a year, three say three to five, and five say one or none.

- 6See for example, Henrik Bresman and Vinika D. Rao, “A Survey of 19 Countries Shows How Generations X, Y, and Z Are — and Aren’t — Different,” Harvard Business Review, 2017-08-25, https://hbr.org/2017/08/a-survey-of-19-countries-shows-how-generations-x-y-and-z-are-and-arent-different.

- 7Hervé Glevarec et al., “Tastes of Our Time: Analysing Age Cohort Effects in the Contemporary Distribution of Music Tastes,” Cultural Trends 29, no. 3 (2020): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09548963.2020.1773247.

- 8The age effect refers to the idea of a particular moment over the course of one’s life (e.g. adolescence or entering adulthood). The generation effect refers to an effect specific to a cohort of individuals and their inclusion in a particular historical moment.

- 9Ewa Mazierska et al., Popular Music in the Post-Digital Age: Politics, Economy, Culture and Technology (New York: Bloomsbury 2018), 3.

- 10Raphaël Nowak, Consuming Music in the Digital Age: Technologies, Roles and Everyday Life (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2016); Sophie Maisonneuve, “L’économie de la découverte musicale à l’ère numérique,” Reseaux 213, no. 1 (2019): 49‑81.

- 11Antoine Hennion, Les Professionnels du disque: Une sociologie des variétés (Paris: Métailié, 1981).

- 12Jacob Thomas Matthews and Lucien Perticoz, L’Industrie musicale à l’aube du XXIe siècle (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2012); Jim Rogers, The Death and Life of the Music Industry in the Digital Age (London: Bloomsbury, 2013); David Arditi, iTake-Over: The Recording Industry in the Digital Era (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014); Maria Eriksson et al., Spotify Teardown: Inside the Black Box of Streaming Music (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019).

- 13Eric Harvey, “Collective Anticipation: The Contested Circulation of an Album Leak,” Convergence 19, no. 1 (2013): 77‑94; François Ribac, “Amateurs et professionnels, gratuité et profits aux premiers temps du Web 2.0: L’exemple de la blogosphère musicale,” Transposition, no 7 (2018): https://journals.openedition.org/transposition/2483; Maria Eriksson, “The Editorial Playlist as Container Technology: On Spotify and the Logistical Role of Digital Music Packages,” Journal of Cultural Economy 13, no. 4 (2020), 415‑427; Guillaume Heuguet, YouTube et les métamorphoses de la musique (Bry-sur-Marne: INA, coll. Études et controverses, 2021).

- 14Concerts et festivals: Quel regard les jeunes posent sur la musique live?, Pass Culture and Prodiss (2022): https://smallpdf.com/fr/file#s=275633fd-23e7-4343-b110-621c688d9ad6.

- 15Antoine Hennion, “Scène rock, concert classique,” Vibrations Hors-série (1991): 101‑119; Philip Auslander, Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture (London: Routledge, 2008); Laure Ferrand, “Comprendre les effervescences musicales. L’exemple des concerts de rock,” Sociétés 104, no. 2 (2009): 27‑37; Yngvar Kjus, Live and Recorded: Music Experience in the Digital Millennium (Berlin: Springer, 2018); Fabian Holt, Everyone Loves Live Music: A Theory of Performance Institutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020); Loïc Riom, “Faire compter la musique. Comment recomposer le live à travers le numérique (Sofar Sounds 2017-2020)” (PhD thesis, CSI Mines-Paris PSL, 2021).

- 16Antoine Hennion et al., Figures de l’amateur: Formes, objets, pratiques de l’amour de la musique aujourd’hui (Paris: La Documentation française, 2000); François Ribac, “L’apprentissage des musiques populaires, une approche comparatiste de la construction des genres,” in Sylvie Ayral and Yves Raibaud, eds., Pour en finir avec la fabrique des garçons. Vol. 2: Sport, loisirs, culture (Pessac: Maison des Sciences de l’Homme d’Aquitaine, 2014); Sylvain Martet, “Découverte et partage des goûts musicaux: Une analyse des parcours d’auditeurs de jeunes adultes montréalais” (PhD thesis, Université du Québec à Montréal, 2017).

- 17Names have been replaced with pseudonyms.

- 18Maarit Kinnunen et al., “Live Music Consumption of the Adolescents of Generation Z,” Etnomusikologian vuosikirja 34, (2022): 65‑92.

- 19Elena Nesti, “‘I Look at Her and I Dance’: Fans Seeking Support in the Movement of a Performing Body,” Ateliers d’anthropologie 50 (2021): https ://journals.openedition.org/ateliers/14876.

- 20Claire Hannecart et al., Rapports des jeunes à la musique à l’ère numérique. Synthèse de l’enquête menée en Pays de la Loire, Le POLE (2015).

- 21On the notion of médiation, see Antoine Hennion, La Passion musicale. Une sociologie de la médiation (Paris: Métailié, 1993).

- 22Gérôme Guibert and Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux, Musiques actuelles: Ça part en live (Paris: IRMA, 2013); Simon Frith et al., The History of Live Music in Britain, Volume 3, 1985-2015: From Live Aid to Live Nation (London: Routledge, 2021); Steve Waksman, Live Music in America: A History from Jenny Lind to Beyoncé (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022).

- 23Guibert and Sagot-Duvauroux, Musiques actuelles; Fabian Holt, “The Economy of Live Music in the Digital Age,” European Journal of Cultural Studies 13, no. 2 (2010): 243‑261; Holt, Everyone Loves Live Music.

- 24Simon Frith, “La musique live, ça compte… ,” Réseaux 141‑142, nos. 2 and 3 (2007): 179‑201

- 25La Diffusion des spectacles de musiques actuelles et de variétés en France, Centre national de la musique (2022): https ://cnm.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/CNM_CDLD_22_MaMA.pdf.

- 26Philippe Lombardo and Loup Wolff, “Cinquante ans de pratiques culturelles en France,” Culture études 2, no. 2 (2020): 50.

- 27Presentation of the DEPS survey as part of the French Ministry of Culture’s symposium “Colloque ‘40 ans de fêtes de la Musique,’” YouTube, 2022-06-16: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A45RmTljHkQ.

- 28Philippe Lombardo and Loup Wolff, “Cinquante ans de pratiques culturelles en France,” 59.

- 29his drop is even greater for the “rock or jazz” category. However, it remains difficult to assess whether this is not an effect of genre classification and in particular the absence of a ”rap” answer option.

- 30Baromètre des pratiques culturelles des Français en matière de spectacles musicaux et de variété, Prodiss and Observatoire du live (2022).

- 31Pierre-Michel Menger, “L’oreille spéculative. Consommation et perception de la musique contemporaine,” Revue française de sociologie 27, no. 3 (1986): 445‑479; Stéphane Dorin, Déchiffrer les publics de la musique classique. Perspectives comparatives, historiques et sociologiques (Paris: Archives contemporaines, 2018).

- 32Hannecart, Rapports des jeunes à la musique à l’ère numérique.

- 33See for example Loïc Riom, “Faire compter la musique. Comment recomposer le live à travers le numérique (Sofar Sounds 2017-2020)”; Sophie Turbé, “Observation de trois scènes locales de musique métal en France: Pratiques amateurs, réseaux et territoire,” (PhD thesis, Université de Lorraine, 2017); Michael Spanu, “Pratiques et représentations des langues chantées dans les musiques populaires en France: Une approche par trois enquêtes autour du français, de l’anglais et de l’occitan,” (PhD thesis, Université de Lorraine, 2017); Kjus, Live and Recorded; Holt, Everyone Loves Live Music; Ben Green, Peak Music Expériences: A New Perspective on Popular Music, Identity and Scenes (London: Routledge, 2022).

- 34Edwidge Millery and her colleagues estimate that almost half of the festivals have been created in the last decade. Edwige Millert et al., “Cartographie nationale des festivals: entre l’éphémère et le permanent, une dynamique culturelle territoriale,” Culture études 2, no. 2 (2023): 1‑32.

- 35Emmanuel Négrier et al., Les Publics des festivals (Paris: Michel de Maule, 2010); Andy Bennett et al., The Festivalization of Culture (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2015).

- 36Baromètre des pratiques culturelles des Français en matière de spectacles musicaux et de variété.

- 37Hannecart, Rapports des jeunes à la musique à l’ère numérique.

- 38Robert Kronenburg, This Must Be the Place: An Architectural History of Popular Music Performance Venues (New York: Bloomsbury, 2019).

- 39In France, journalistic work has shown that both the main concert venues and the most important festivals are controlled by a few large international groups: https ://www.vousnetespaslaparhasard.com/. See also: Fabian Holt, Everyone Loves Live Music.

- 40Adam Behr and M. Cloonan, “Going Spare? Concert Tickets, Touting and Cultural Value,” International Journal of Cultural Policy 26, no. 1 (2018): 95-108; Marie Connolly and Alan Kreuger, “Rockonomics: The Economics of Popular Music,” Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture 1 (2006): 667‑719.

- 41The Enquête sur les pratiques culturelles 2018 shows that 90% of 15–24-year-olds listen to music on digital media (digital files, online services). See DEPS, Chiffres clés 2022, French Ministry of Culture, 2022. MIDiA reports that in the UK, 53% of 16–19-year-olds use Spotify on a daily basis. Broadly speaking, studies also agree on the fact that under 26s pay to access a streaming package. Nevertheless, if streaming listening is widely used in this age group, other practices are observed. Still according to DEPS figures, 24% of 15–24-year-olds listen to music on physical media (CDs, cassettes, vinyl). On this topic, see also Raphaël Nowak, Consuming Music in the Digital Age; Quentin Guilliotte, “La persistance de l’attachement aux biens culturels physiques,” Biens symboliques 9 (2021): https://journals.openedition.org/bssg/864; Baromètre de la consommation de biens culturels dématérialisés, Hadopi, 2021.

- 42For example, for the UK see Mark Mulligan, Gen Z. Meet The Young Millennials, MiDiA, 2017. For the US see Ana Dartaru, “What Clicks with Gen Z,” Creatopy, 2022-07-22: https://www.creatopy.com/blog/whitepaper-what-clicks-with-gen-z/.

- 43Mehdi Bautier, “Réseaux sociaux: les 16-25 ans abandonnent Facebook pour TikTok,” Diplomeo, 2022-02-03: https://diplomeo.com/actualite-sondage_reseaux_sociaux_jeunes_2022?utm_source=blogdumoderateur&utm_medium=siteweb&utm_campaign=etude-usage-reseaux-sociaux-generation-z-2022&utm_content=lien&utm_term=Diplomeo.

- 44We can also note that we still know little about the proliferation of apps that aim to accompany the concert experience: setlist sharing, online ticketing, recommendations, etc.

- 45Nicolas Nova, Smartphones (Geneva: Métis presses, 2020).

- 46Frédéric Trottier-Pistien, “‘C’est ça le futur des soirées?’ Les musiques électroniques de danse à l’épreuve du livestream et de la COVID-19,” Communiquer, no. 35 (2022): 81‑99; Romain Bigay, “Ce que le livestream fait au live,” Communiquer, no. 35 (2022): 25‑37; Gérôme Guibert and Martin Lussier, “La musique live en contexte numérique. Captation, diffusion, valorisation, usages,” Communiquer, no. 35 (2022): 1‑6; Ariane D’Hoop and Jeannette Pols, “‘The Game is On!’ Eventness at a Distance at a Livestream Concert during Lockdown,” Ethnography (2022): https://doi.org/10.1177/14661381221124502; Gérôme Guibert, “Live Performance and Filmed Concerts: Remarks on Music Production and Livestreaming Before, During, and After the Public Health Crisis,” Ethnomusicology Review 24 (2023): https://ethnomusicologyreview.ucla.edu/journal/volume/24/piece/1099.

- 47Étude prospective sur le marché du livestream musical en France, Arcom and CNM, 2022.

- 48Les Français et les spectacles vivants, Prodiss, 2022.

- 49For an overview, see Loïc Riom and Michael Spanu,“Les nouvelles médiations audiovisuelles de la musique live: Formats, industrie et patrimoine culturel numérique,” SociologieS, to be published.

- 50On these developments in South Korea, see H. Won, “La possibilité d’un nouveau modèle économique avec les concerts en ligne: Un regard socio-économique sur la K-Pop en Corée du Sud,” SociologieS, to be published.

- 51Anne Danielson and Yngvar Kjus, “The Mediated Festival: Live Music as Trigger of Streaming and Social Media Engagement,” Convergence 25, no. 4 (2019): 714‑734.

- 52In Art Worlds, Howard Becker already mentioned this complicated relationship between musical production and the time available to musicians on recording media. Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds (Berkely and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982).

- 53On how YouTube is used by artists, see in particular Caroline Creton, “Approche communicationnelle des scènes musicales locales face à l’offre médiatique numérique: le cas nantais” (PhD thesis, Université de Rennes 2, 2019); Caroline Creton, “L’image au cœur des pratiques communicationnelles des scènes musicales,” Revue française des sciences de l’information et de la communication, no. 18 (2019): https://journals.openedition.org/rfsic/8262#quotation.

- 54Brian Hracs et al., “Standing out in the Crowd: The Rise of Exclusivity-Based Strategies to Compete in the Contemporary Marketplace for Music and Fashion,” Environment and Planning A 45, no. 5 (2013): 1144‑61; Nancy K. Baym, Playing to the Crowd: Musicians, Audiences, and the Intimate Work of Connection (New York: NYU Press, 2018); Loïc Riom, “Discovering Music at Sofar Sounds: Surprise, Attachment, and the Fan–Artist Relationship” in Tamas Tofalvy and Emília Barna, eds., Popular Music, Technology, and the Changing Media Ecosystem (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020): 201‑216.

- 55In 1991, Antoine Hennion noted these different mediations which create the artist-audience relationship: “These asymptotic set-ups are performative patterns, efforts to ‘produce’ music, by defining in passing, in the strongest sense of the term passage, its subjects, objects and means.” Antoine Hennion, “Scène rock, concert Classique.”

- 56Here I adopt a formulation of Antoine Hennion for examining music theory lessons. Antoine Hennion, Comment la musique vient aux enfants. Une anthropologie de l’enseignement musical (Paris : Anthropos, 1988).