Introduction

Everyone knows that music is an art. Music professionals, whether artists or entrepreneurs, are well aware that music is also an industry. “Generally speaking, the industrial economy concerns those activities combining factors of production (facilities, supplies, work, knowledge) to produce material goods intended for the market1https://www.insee.fr/en/metadonnees/definition/c1426.” The industry aims at mass production of goods, which requires many human, tangible and also financial resources. In practice, we also refer to the “music industry” and more precisely the “recorded music industry”, which is traditionally divided into four stages: artistic creation; industrialisation, i.e. transforming a work into a reproducible product; promotion and, lastly, marketing.2Curien N. & Moreau F., L’Industrie du disque, Paris, La Découverte, coll. Repères, 2006, p. 5. Funding and investment feed each of these links, since creators and businesses need funds to carry out their projects. Industrialisation presupposes a financialisation, understood here, without any derogatory connotation, as a collection of the necessary funds to conduct economic activities. In France and abroad, while artistic production is based on intellectual work, it also involves smaller or larger commercial enterprises, which are generally established in the form of companies. These companies inevitably include shareholders, who hope for a return on investment.

The industrialisation and financialisation of music is not new. It is striking in the United States: Edison Records was founded in 1888 by Thomas A. Edison; Sony Music originated from the American Record Corporation, founded in 1929 as a result of the merger of several record companies. However, one practice that has emerged over the past five years, attracting the attention of various journalists and players in the music sector, is the acquisition of music catalogues at exorbitant prices and the intervention of new protagonists, who are financial stakeholders, such as investment funds. These catalogues are sold either to traditional players (labels or publishers)3« Droits musicaux : Bob Dylan vend son catalogue à Sony », Les Échos, 25 January 2022, online: https://www.lesechos.fr/tech-medias/medias/droits-musicaux-bob-dylan-vend-son-catalogue-a-sony-1381629 or to investment funds managed by music professionals4« Justin Bieber vend son catalogue musical pour plus de 200 millions de dollars », Les Échos, 25 January 2023, online: https://www.lesechos.fr/tech-medias/medias/justin-bieber-vend-son-catalogue-musical-pour-plus-de-200-millions-de-dollars-1900262. Some of these transactions involve “back catalogues”, i.e. titles that make a dramatic comeback in exploitations several years after their release.

The economic dimension of music appears very clearly through copyright collections. According to Sacem, “With the resumption of live shows and the sustained growth of digital technology, collections have risen by 34%. This represents an increase of nearly €300 million compared to 2019. Digital rights are up 38% again, and general rights are almost back to pre-crisis levels5Sacem, Annual report 2022, June 2023, p. 18, online: http://flyer.sacemenligne.fr/RA/2022_FR/Sacem_RA_2022.html.” Moreover, although the health crisis was detrimental to the performing arts economy and aggravated the record economy, it was profitable for the online trade of music6Sacem, Annual report 2021, June 2022, p. 14, online:http://flyer.sacemenligne.fr/RA/2021_FR/Sacem_RA_2021.html#p=1. Digital technology now accounts for more than one-third of global music rights collections7CISAC, Rapport sur les collectes mondiales, 2022, p. 23, online:https://www.cisac.org/fr/services/etudes-et-recherches/rapport-sur-les-collectes-mondiales-2022#:~:text=Les%20revenus%20du%20num%C3%A9rique%20ont,conclus%20avec%20les%20plateformes%20num%C3%A9riques. The development of platforms makes it possible to multiply the territories where works are disseminated. This “platformisation” also reduces the problems related to online IP infringement, since music enthusiasts can access extremely large and diverse music libraries quickly, simply and at a relatively low cost. However, music copyright infringement, especially online, still remains an important issue for rights holders and public authorities. Despite the fact that the synchronisation right is not enshrined in French law, synchronisation, i.e. the integration of music in films, series and advertisements, is very common and involves the creation in practice of synchronisation contracts at international level, including in France, which offers sources of income. We should also add that, given the diversity of its styles and genres, music quite simply speaks to a very large audience, regardless of age, nationality or social situation. Many songs can be marketed worldwide, especially those in English, but also in other popular languages, such as French at international level. From a financial perspective, recorded music offers alternative asset classes to traditional investments, such as in property.

The press and a recent study highlight the explosion in the number of transactions and the increase in the amounts raised for catalogue acquisitions8Cole H., Davies K. and Turner D., « Deux décennies d’achats de catalogues musicaux », CNMlab, 6 October 2022, online: https://cnmlab.fr/onde-courte/deux-decennies-dachats-de-catalogues-musicaux/.. This study deals with the acquisition of music rights, a changing market that has been thrown into turmoil in recent years with the emergence of investment funds which increase purchasing capacities while renewing acquisition objects and methods.

What is the situation in France?

As the world’s sixth-largest market in the music industry9IFPI, Global Music Report 2023, p. 10, online: https://ifpi-website-cms.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/GMR_2023_State_of_the_Industry_ee2ea600e2.pdf, the French music rights acquisition market is challenged by these practices, mainly originating from the United States and the United Kingdom. The multiplication of these investment funds, whose means and acquisitions are constantly increasing, seems to stop on France’s doorstep. Beyond the Anglo-American stakeholders, local and sometimes ingenious initiatives are appearing all over the world. All over the world, that is, except in France. On the one hand, French investment funds seem hermetic to music assets and, on the other, the French market and its assets do not yet appear to be invested by foreign funds, despite what certain statements lead us to believe, including those by the renowned entrepreneur Merck Mercuriadis in 2021: “I’d love to buy songs by Françoise Hardy, Jacques Dutronc, Charles Aznavour, Joe Dassin, Téléphone, Air, Daft Punk, Justice, Jacques Brel, Georges Moustaki, Charles Trenet, Édith Piaf, Serge Gainsbourg, Renaud and Les Rita Mitsouko. […] With 88 specialists to handle 64,000 songs, my company is more capable than multinationals that have small teams for millions of titles10Lutaud L., « Le mercato des tubes bat son plein », Le Figaro, 21 July 2021, online: https://www.lefigaro.fr/musique/le-mercato-des-tubes-bat-son-plein-20210721..”

Music rights, understood as copyright (including the share accruing to authors and music publishers) and related rights (including the share accruing to performers and producers of phonograms) are part of a financial, and more specifically, an investment approach: an entity, natural or legal person, will pay a sum of money in the hope of making a monetary gain through the return of these rights. The increasing use of the asset concept attests to this financial dimension11Quiquerez A., La Titrisation des actifs intellectuels, Larcier, pref. N. Binctin & A. Prüm, 2013.: music rights, just like property rights or financial securities, are assets that can be called music assets by capillarity. A financial approach drives all intellectual property, including literary and artistic property12Binctin N., Droit de la propriété intellectuelle, Paris, LGDJ, coll. Manuel, 7th edition, 2022.. The use of the asset concept seems quite well disseminated in the music industry today, albeit seemingly less so in France due to a general distrust of finance and, undoubtedly, a lack of expertise in this discipline. Investing in music assets can take the form of a direct acquisition, in other words a purchase on a personal basis of a music catalogue. This notion of catalogue, which is also known in the audiovisual field, is a notion resulting from practice rather than from legal texts. It commonly refers to a set or “collection” of copyright (and/or sometimes related rights) on music or songs by the same author (or artist) or, in other cases, different authors (or artists). As with audiovisual rights catalogues, music catalogues of various artists usually have a distinctive name in order to identify them. This emerging notion both in France and abroad deserves a legal analysis in its own right13Cf. Gautier P.-Y. & Blanc N., Droit de la propriété littéraire et artistique, LGDJ, 2021, no. 754, 755 and 763.. In our opinion, a music catalogue corresponds to the notion of de facto universality, a set of goods forming a complex legal entity[14]. This qualification of de facto universality highlights the fact that catalogue acquisition transactions can be carried out through a single contract, i.e. the sales contract, without having to conclude a contract for each title included in the catalogue. The buyer of the catalogue can then resell it in whole or in part. The sale of music catalogues is organised in a real market, bringing together various sellers (publishers, authors, heirs of authors, etc.) and buyers (publishers, investment funds, etc.).

Music rights, more precisely copyright and related rights on their economic component, excluding moral rights, are property. Indeed, they are subject to a property right and are in the legal trade. They can therefore be assigned. Two types of assignment are possible:

– an assignment of the economic rights on one or more work(s), interpretation(s) or recording(s). The assignment contract therefore concerns only economic rights and not other assets. We could refer to this transaction as an “isolated assignment”;

– an assignment of the business, i.e. all of the tangible or intangible elements of the business, which may include copyright or related rights. Assignment and music publishing contracts are transferred to the assignee14According to French law: Art. L. 132-16 of the Intellectual Property Code.. Some of these transactions are carried out as part of collective proceedings15For example, in 2016, as part of a liquidation procedure, Believe Digital acquired the assets of Naïve and the royalties not paid to the artists, excluding debts and the book business..

A real security can also be established on intellectual property rights, more specifically a pledge. A pledge is the use, as security, of an obligation, an intangible movable property or a set of present of future intangible movable property. For music assets, this is the case of the copyright security agreements sometimes requested by US investment banks on the music rights of the film studios they finance16For example, the Washington Copyright Office mentions such an agreement between DreamWorks Music Publishing, LLC and JPMorgan Chase Bank..

In this study, we will try to understand France’s place in the international market in terms of:

– the different structural, technical and legal features of the acquisition market;

– the functioning of its stakeholders and its assets using examples of financial transactions;

– the risks associated with these transactions. These economic or extra-economic risks are likely to concern both creators and companies, but also the general interest, especially with regard to what can be called “French artistic heritage” if we follow a cultural approach, as can be more commonly found in the literary, pictorial or architectural field.

This research was carried out using first-hand practical documents and consultation with professionals. The transactions discussed are complex in terms of their legal and financial structure and are based on very voluminous legal documentation17The Hipgnosis Songs Funds Limited prospectus alone contains 245 pages.. To understand current practices, we will first draw up an inventory of the stakeholders and contracts in France (1) and of the investment transactions in music assets (2). We will then analyse the specificities of the French acquisition market (3) before identifying the legal issues and risks, while proposing solutions to anticipate or resolve them (4).

Stakeholders and contracts in France

Notice to the reader: this first section is primarily intended for non-specialists; it lays the foundations of music law that structures the financial arrangements described in the rest of the article. If you already have a good grasp of the basics of literary and artistic property, you may go directly to section 2.

In order to potentially transpose financial arrangements into the French music industry, we first need to identify how chains of rights currently work. As with the audiovisual and cinematographic field, music is subject to chains of rights that are more or less long depending on the work. This involves transferring literary and artistic property rights (copyright and related rights), more specifically exclusive exploitation rights18Art. L. 123-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code; for related performers’ rights, the Code refers to “exploitation rights”: Art. L. 212-3-1 of the Intellectual Property Code., through the contractual tool. Contracts are essential instruments for organising relationships between parties, managing risks and providing for financial compensation. In this section, we will identify the stakeholders of chains of rights (1.1) and the contracts (1.2).

Stakeholders of chains of rights

Literary and artistic property law distinguishes between two natural persons19Natural persons are human persons, as opposed to legal persons (companies registered in the trade and companies register, associations declared at the prefecture, etc.).at the origin of songs:

– the author of the work: the natural person who created the work of the mind, in other words the literary and artistic work. In principle, the author is the original owner of the copyright, whether in the form of economic rights or moral rights. Authors include: the composer of the music, the songwriter. Copyright is only recognised in the presence of an original work of the mind. French case law defines originality as the imprint of the personality of a work’s author. There may well be co-authors and co-ownership of rights, which is frequently the case for musical works: the work is both the creation and property of the composer(s) and/or the songwriter(s); it is then a collaborative work. On the other hand, when a song incorporates a pre-existing text, without collaboration between the composer and the songwriter, it is a composite work20CA Paris 12 January 2021, no. 15/19803.. In French law, a legal person (company, investment fund, for example) cannot have the status of author – a factor which serves to protect creators21Civ. cass. 1, 15 January 2015, no. 13-23.566, ruling that “a legal person cannot have the status of an author” – whereas in American law, under the “work made for hire” regime, the company that employed the author is considered both the author and the copyright holder of the work. The author is the holder of moral rights, which are non-transferable, unlike economic rights. The sale of a music catalogue therefore cannot include moral rights;

– the performer: the natural person who performs the musical creation. Performers include, in particular: singers, musicians, conductors, DJs. Performers benefit from related rights, i.e. economic and moral rights, which are similar but distinct from copyright. The performance must be of a personal nature in order to be protected22Civ. cass. 1, 24 April 2013, no. 11-20.900..

The same natural person can be an author and a performer (songwriter/composer/performer).

Several types of company can also be distinguished:

– (music) publishers: these are companies that assign the economic rights of authors, under a publishing contract, and are responsible for marketing the work to the public. The music publisher enters into contracts with producers, the media and advertisers to disseminate the work. The publisher is entitled to what is called in practice the “publishing share”, i.e. the share due to the marketing of a music work. Whereas the rate of this share is freely negotiable between the author and the publisher for certain rights (synchronisation and graphic reproduction, for example), it is defined by collective management bodies for other rights (public execution right, for example, and according to the contributions made by the rights holders);

– phonogram producers: also referred to in practice as a music label, a record company, a phonographic producer or simply a producer. It is “the natural or legal person who has the initiative and responsibility for the first fixation of a sound sequence23Art. L. 213-1, (1), of the Intellectual Property Code..” The producer of phonograms enjoys the rights to the recording, which are related rights, and therefore intangible or intellectual property rights; these rights are also considered as intangible property. These rights are to be distinguished from physical property rights of which the producer is also owner: he is the owner of the master recording; this tangible property refers to the original recording from which a work is reproduced. In France there are three main players: Universal Music Group, Sony and Warner Music France, but there are also numerous independent labels. However, some performers self-produce their recorded music, i.e. they take care of the recording and mixing activities themselves24Réguer-Petit M., Monfort M., Audran M., « Étude exploratoire sur l’autoproduction des artistes de la musique », Agence Phare on behalf of the French Ministry of Culture, final report, 2019, online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/a238ktfg7r23/6aVOOhvUzepN4jXnc68wMS/ef4fa5e6886107e94ee3436c0165dbde/Phare_-_Rapport_final_-_Autoproduction_musicale_DGMIC.pdf.. Self-production allows performers to better control the ownership of their rights and, if they wish, to easily transfer them, on their own or “within” a catalogue. By extension, the label is the registered trademark of the phonogram producer, and the latter can manage several labels that are protected and harnessed as trademarks;

– music distributors: these are companies responsible for distributing music in physical stores and/or on online platforms. They can therefore be physical and/or digital distributors. As part of their service offering, some distributors also offer to promote this music, i.e. to conduct marketing campaigns, especially online;

– performing arts entrepreneur : a performing arts entrepreneur is any person who carries on an activity of operating performance venues, producing or disseminating performances (particular of a musical nature), alone or in the context of contracts concluded with other performing arts entrepreneurs, regardless of the management method of these activities, whether public or private, for-profit or non-profit;

– audiovisual producer: the natural or legal person who takes the initiative and responsibility for the production of an audiovisual work25Art. L. 132-23 of the Intellectual Property Code.. Audiovisual works are cinematographic works and other works consisting of animated sequences of images, either with or without sound26Art. L. 112-2 (6) of the Intellectual Property Code.. Audiovisual producers often use synchronisation, i.e. the incorporation of pre-existing music into the audiovisual work (film, advertising, etc.).

Large groups in the industry generally have separate entities within them for music publishing (publishing activity), music production (recording activity) and distribution. According to what is now commonly referred to as the “360° strategy”, the goal for major players and music labels is to diversify their activities as much as possible to create “multi-revenue” sources.

It should be noted that the French term “réalisateur artistique” refers to the professionals (natural persons) responsible for the studio production of the master recording. In the United States and the United Kingdom, the “réalisateur artistique” is called the “producer”. Producers are not responsible for fixing the work on a medium or for distributing, exploiting or financing it. Some producers negotiate to obtain a part of the copyright when they participate in the creation of the musical work.

To manage part of their economic rights and collect their royalties, some authors and publishers join a collective management organisation. This is any organisation whose sole or main purpose is to manage copyright and/or rights related to copyright on behalf of several rights holders, for the collective benefit of the latter, which is authorised for this purpose by law or by way of assignment, license or other contractual agreement27Directive 2014/26/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on collective management of copyright and related rights and multi-territorial licensing of rights in musical works for online use in the internal market.. This organisation is controlled by its members or is a non-profit association. It collects and distributes income among the right-holder members according to the contributions made to it. In France, music authors and publishers can join Sacem for public performance rights (DEP) from public dissemination (concerts, for example) and for mechanical reproduction rights (DRM) from the purchase of records. However, Sacem does not manage the synchronisation right or the graphic reproduction right28The graphic reproduction rights relate to the reproduction of the score and lyrics, for example for karaokes and platforms, these rights are not subject to collective management, but to individual management at publisher level.. In addition, related rights are also subject to collective management, whether they are the rights of performers (ADAMI, SPEDIDAM) or of phonogram producers (SCPP, SPPF).

Collective management bodies differ on both sides of the Atlantic. In France, we have a single company in charge of performance and reproduction rights for publishers, but also for songwriters. In the US, performance rights and mechanical rights are redistributed by specific organisations: “Performance Rights Organization (PRO)” for the former (ASCAP, BMI, etc.) and “Mechanical Pay Sources (MPS)” for the latter (MLC, for example). Mechanical Pay Sources only pay the publishers, who are then in charge of paying the songwriters.

To sum up, the main music rights, whether droit d’auteur (author’s right) in France or “copyright” in the US and UK, are as follows:

– copyright: consists of mechanical rights for fixing the work on a physical or digital medium, performing rights for disseminating the work on the radio, and synchronisation rights (use for TV, cinema, adverts, etc.). Holders of these rights include composers, songwriters and their publishers;

– the related rights of the performer (singer, musician), which are generally transferred to the producer of phonograms: the performer retains his pecuniary rights relating to his performance, but assigns to the phonogram producer the right to exploit his rights to the interpretation of the work;

– the related rights of the phonogram producer: these comprise (i) recording rights or reproduction rights for record sales, streaming and downloads (ii) performance rights when the work is disseminated to the public and (iii) synchronisation rights. Record labels hold these rights.

Successive waves of acquisitions in recent years have gradually shifted towards more and more specific rights, thus opening up a fragmentation of these rights. We can illustrate this fragmentation by the recent acquisition of some of David Foster’s rights by Hipgnosis Song Management. Indeed, this company “only” acquired the writer’s share of performance of David Foster, i.e. the songwriter’s share corresponding to his performance rights. The object of this transaction was, however, rather vast since it was the representation of all of the artist’s works.

The contracts

There are different types of contract29Bouvery P.-M., Les Contrats de la musique, Paris, CNM Éditions, 8th edition, 2022., including for copyright:

– the assignment and music publishing contract: this is the contract by which the author of a musical work, or his right holders, exclusively assigns to a music publisher certain rights to his work, these rights being covered in the contract, subject to contributions to collective management bodies;

– the publishing preference agreement: this agreement confers a right of preference, a right of pre-emption, called an “option” in practice, for the benefit of the publisher. The author undertakes to assign to the publisher, if he wishes, his rights on his future works for a certain period, which is five years at most in French law30Art. L. 132-4 of the Intellectual Property Code.. The contract must define how the author accepts that his works are marketed and promoted;

– co-publishing agreement: this agreement is between several publishers. In some cases, the author is co-publisher. The content of the agreement specifies the role of each co-publisher and the distribution of revenue and expenditure;

– the sub-publishing agreement: it allows the original publisher of the work (assignee of the author’s rights) to negotiate with a foreign publisher for the marketing and promotion of the work in a specific territory;

– the management agreement: the author grants the publisher the right to administer his musical works for a fixed period in return for a commission. There is no assignment of rights here: the publisher undertakes to manage the author’s catalogue and to follow up with collective management bodies. This is an interesting option for authors who wish to remain the owner of their rights while enjoying administrative support;

– the distribution agreement: a contract generally concluded between a company or an association holding the rights and a distributor, with a view to distributing in physical and/or digital form. In some contracts, the distributor may also commit to promoting music;

– the synchronisation agreement: an operating agreement whereby the owner of the copyright (often a music publisher) grants an audiovisual producer the right to use and incorporate a pre-existing music work in an audiovisual work.

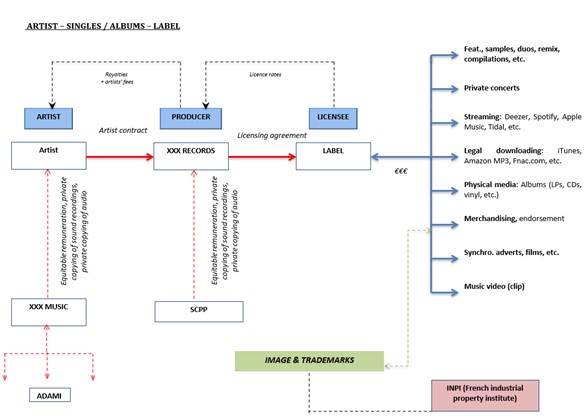

For related rights of performers, the following contracts exist in particular:

– the artist contract: this contract is concluded between an artist and a phonographic producer for the recording and use of his performances. It constitutes an employment contract and the artist receives a salary for the recording sessions. This contract also involves a transfer of rights to allow the recordings to be used for proportional royalties;

– the licensing agreement: when an independent producer has produced one or more recordings with the performer, he obviously wants to ensure the marketing thereof. He could make copies of the record himself and promote and distribute them on his own, but this task involves considerable experience and financial resources. This is why producers turn to labels (record companies) by concluding licensing agreements with them. A licensing agreement is an agreement whereby the owner of a recording (the producer) gives another party (the licensee) the right to reproduce and market said recording. This right may be exclusive or non-exclusive;

– the association or company contract: rather than being an individual entrepreneur, at a certain stage of the project’s economic development, the performer will create an association or a commercial company. On the one hand, under French law, the association contract will give rise to an association which will be declared at the prefecture and which will therefore obtain legal status. The performer will have to find members for this association, but no capital is needed. On the other hand, the company contract will involve the creation of a commercial company, which can be, if it is a VSE (very small enterprise), a sole proprietorship (single-shareholder company or a one-person limited liability undertaking) or a multi-personal company (simplified joint stock company, limited liability company). The articles of association or company reflect the association or company contract. The author or artist assigns (assignment) or contributes his rights (contribution) to the company.

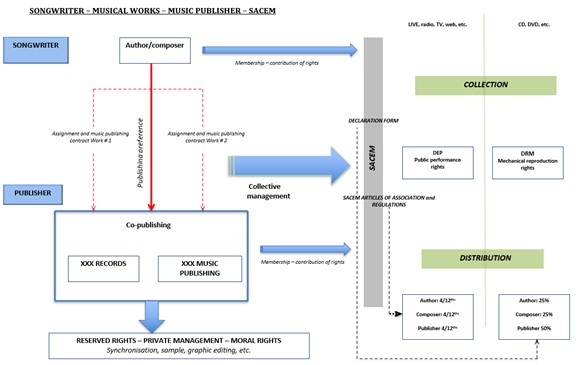

DIAGRAM OF STAKEHOLDERS AND CONTRACTS31The authors would like to thank Maître Marc-Olivier Deblanc for these diagrams and for his permission to reproduce them.

Contracts relating to literary and artistic property rights are generally entered into for pecuniary interest, i.e. they entail financial compensation. Collective management bodies distribute these rights by paying the amounts due to their members in accordance with their statutes and based on the contributions made to their benefit by the rights holders. Their members therefore receive a sum of money for the use of the work or performance, bearing in mind that certain rights are always managed individually by music publishers (such as synchronisation or graphic reproduction of works) and phonographic producers. Authors and their rights holders (music publishers, in particular) receive copyright income. Performers and their rights holders (phonogram producers) receive income from their related rights.

Investment transactions in music assets

Investment transactions in music assets are often part of complex arrangements involving different entities (particularly companies), various contracts and ancillary transactions that are diverse (audit, valuation, tax procedures, etc.). Contractual relations unite the parties involved in these transactions that combine artistic property with finance. The purpose of the financial transaction carried out by contracts must be rigorously identified, depending on whether it is, for example, a subscription for shares in a company, the acquisition of intellectual property rights or royalty rights. We call investments “direct” if they involve the acquisition of music assets (2.1) or “indirect” when other assets, such as shares or royalty receivables, are acquired (2.2).

Direct investments in music assets

The following may invest directly in music assets: intellectual property holdings (2.1.1), companies or investment funds (2.1.2) and more specifically securitisation funds (2.1.3), but also joint venture companies (2.1.4).

Acquisitions by intellectual property holdings

Some corporate groups or individuals establish an intellectual property holding company. This is an entity whose specific purpose is to hold and exploit intellectual property rights and, more broadly, intangible assets (image rights, domain names, websites, etc.). Most often, the latter are ad hoc commercial companies, but we observe that certain music asset acquisitions are sometimes made in practice through common law trusts (a system based on case law) or special status entities32Example of Anstalt in Liechtenstein..

For example, Kobalt Music Copyrights Sarl is a Luxembourg commercial company belonging to the Kobalt group, created in 2011, and whose object is music publishing and rights management. This entity holds a large volume of copyrights, mainly on successful songs in English. David Guetta sold his publishing rights to this entity in 2018. Kobalt Music Copyrights Sarl does not appear to be a real investment fund, but rather a special entity tasked with acquiring music rights. Nevertheless, this entity needs investors – shareholders – to make acquisitions at significant prices.

Acquisitions by investment companies or investment funds

Some music rights acquisitions are not made by operating commercial companies, such as music producers or banks, but by companies or entities that invest in assets. According to European law33Directive 2011/61/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 on Alternative Investment Fund Managers., these are alternative investment funds in that they raise capital from a number of investors to invest it, in accordance with a defined investment policy, in the interest of these investors. They are not undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities (UCITS), since their assets are not composed of financial securities, but of literary and artistic property rights.

Hipgnosis Songs Fund Ltd (HSFL) was founded by the renowned artist manager, Merck Mercuriadis. HSFL is a Guernsey-registered investment company created to provide investors with direct exposure to songs and associated music intellectual property rights. The company raised a total of over £1.05 billion through its IPO on the London Stock Exchange on 11 July 2018 and subsequent issues in April 2019, August 2019, October 2019, July 2020 and September 2020. In September 2019, Hipgnosis transferred all of its issued share capital to the premium listing segment of the official list of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and to the premium segment of the London Stock Exchange of the main market, and in March 2020, the fund joined the FTSE 250 index. Its prospectus is very clear about its activities: “The Company invests in Catalogues of Songs and associated musical intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to, master recordings, rights over future Songs that are acquired by the Company through the payment of Advances to such songwriter and secured against the future Songs, and producer royalties) and seeks to acquire 100 per cent of a songwriter’s copyright interest in each Song, which would comprise their writer’s share, their publisher’s share and their performance rights. The Company, directly or indirectly via third-party portfolio administrators, enters into licensing agreements, under which the Company receives payments attributable to the copyright interests in the Songs which it owns. Such payments may take the form of royalties, licence fees and/or advance payments. The Company focuses on delivering income growth and capital growth by pursuing efficiencies in the collection of payments and active management of the Songs it owns within its Portfolio.”. The fund is managed by Hipgnosis Songs Ltd, made up of a team that specialises in the music market.

This recent transaction, which was widely communicated about, was not entirely new. For example, Round Hill Music Royalty Fund issued shares in 200034Round Hill Music Royalty Fund, Prospectus, 2000.. This company created in Guernsey has invested in the copyrights of a songwriter on a music composition or song and the recording rights of the music composition or song and all rights and assets considered incidental thereto by the investment manager. The company has invested in small to medium-sized catalogues (typically 100 to 1,000 titles) that are diversified by artist, genre and age. The assets have generally reached a stable income and are not subject to the natural decline in income and value that typically occurs during the first ten years of a composition’s life.

Created in Canada in 2018, Barometer Music Royalty Fund I Inc. was a fund that purchased music publishing rights to North American songs. In 2021, this fund was sold to AP Music Royalties Fund (APMRF), a regulated alternative investment fund created in Liechtenstein and managed by the Swiss management company Alternative Partners. APMRF acquires the copyright indirectly by subscribing to bonds or by acquiring securities issued by companies exclusively dedicated to the acquisition of catalogues.

Interesting for its “two-tier” structure, EICO Music Fund is a “sub-fund” of a Maltese SICAV that is a shareholder of EICO Publishing Ltd, which acquires publishing rights after valuation. The acquisitions currently focus on international and Italian catalogues, and the fund is considering investing in French songs. ICM Crescendo Music Royalty Fund is a Californian investment fund that focuses on acquiring assets generated from streaming platforms such as YouTube, Spotify and Pandora35https://www.icmassetmanagement.com/icm-crescendo-music-royalty-fund.. The fund, launched in 2021, invests in all genres, including pop, electro, R&B, country and rock.

Pophouse Entertainment Group AB is a company incorporated in Sweden that acquires copyright and related rights in songs, most of which are Swedish. The business model is not to make a passive investment, but to develop the brand image of singers and to propose strategies for optimising revenues, based in particular on technological tools36Cf. the interview with Parham Benisi, partner of Pophouse Investments, 2 June 2022, online: https://pophouse.se/news/interview-with-pophouse-investments-partner-parham-benisi.. The acquisition may relate to part of the rights and is also presented as a joint venture37Aswad J., “Avicii Estate Sells 75 % of Late DJ’s Catalog to Pophouse”, Variety, 28 September 2022, online: https://variety.com/2022/music/news/avicii-family-sells-catalog-pophouse-1235386629..

Funds such as Armada Music’s BEAT (focused on dance), Jamar Chess’s Wahoo Music Fund One (Latin music), Blackx Music Fund in Singapore (Asian music) and Multimedia Music (film and TV music) have all been launched over the past 18 months with the following objectives: to leverage their expertise in the genre and their industry relationships to buy rights to songs of a category and make a return on investment38Dilts Marshall E., “Niche-Focused Funds Are the Next ‘Natural Step’ in Music Investment”, Billboard, 14 June 2023, online: https://www.billboard.com/pro/music-investment-funds-niche-genres.. This type of fund could inspire the creation of an investment vehicle specialising in French songs.

From a practical point of view, the creation of an investment fund dedicated to the acquisition of literary or artistic property rights meets financial objectives. On the one hand, the assignor (author, performer, publisher, producer) quickly receives a price for the assignment of his rights to the fund, without waiting for the collection of royalties for a period of time. On the other hand, the fund will collect royalties that it will redistribute to investors over time, generally in the form of dividends.

Many funds acquiring copyrights on musical works (mainly American or British) are confidential, but are often referenced on official registers (Washington Copyright Office, Sacem repertoire, etc.) and mainly involve songs in English.

Acquisitions by securitisation funds

The securitisation of music assets is a special purpose vehicle (SPV), an entity created and operating for a specific purpose. In a securitisation context, this SPV is also called a “securitisation fund”, a type of investment fund. Generally speaking, securitisation is a complex arrangement by which a company (bank, supplier, etc.) assigns – or transfers – receivables to an SPV, which is a company, fund or trust specifically dedicated to securitisation. This SPV thus acquires these receivables thanks to the money received from the subscription by investors to financial securities that are typically bonds or units with an interest rate. The transferring company immediately receives a sum of money from the SPV. The latter will receive the money from the payment of the receivables at maturity, this money is then paid to the investors for several years as their remuneration (repayment of the capital of the financial securities and payment of interest). Securitisation is often referred to as the issue of asset-backed securities (ABS), although it should be noted that there are different securitisation categories.

Insofar as a specific return is generally promised to investors in securitisation funds, the audit and valuation of securitised assets are key processes for the success of the transaction. Applying securitisation to artistic assets is not economically obvious since this asset class generally generates irregular income, unlike loans, which are typically securitised assets. For securitisation to be a success, the financial valuation, i.e. the anticipation of income, is an essential step before deciding whether or not to use securitisation. Independent valuators determine the value of a catalogue by projecting future royalty streams and using a discounted cash flow method to determine their current value39Dilts Marshall E., “The Woman Behind Music’s Most Important Catalog Valuations Explains How It’s Done”, Billboard, 1 April 2023.. Valuators are also generally called upon to carry out annual valuations.

The first securitisations in the music sector were made on copyrights by the authors themselves (composers and songwriters). SESAC, a US rights management company, is also active in securitisation through several transactions. It is one of the largest public performance rights management companies in the United States. More recently, music publishers, funds or investment companies have securitised copyrights on songs by different authors and singers. Professionals, such as rating agencies, refer to this practice as “music royalty ABS”. This type of transaction enables copyright owners and SESAC to raise significant funding. Unlike a loan, there are no repayment obligations The copyrights are transferred to the SPV so that, in the event that the assignor or an administrator of the catalogue goes bankrupt, the SPV can entrust the exploitation of the rights or assign them to third parties. In other words, the bankruptcy of assignors or other stakeholders should not have an impact on the ownership of rights and the generation of income. The fact that the SPV has the intellectual property rights allows the securities to benefit from a good credit rating from rating agencies, insofar as these assets are supposed to have a certain economic value.

The US investment banker, David Pullman, became known for the structuring of Bowie Bonds, launched in 1997. In an innovative way, David Bowie transferred his copyrights on 25 albums (287 titles) to an ad hoc US-based company that paid him €55 million. In return, the investor in this company held a bond with an interest rate of 7.9%, remunerated through royalties from these works. David Pullman then reproduced a similar arrangement for other composers and performers, such as James Brown, Marvin Gaye, Ron Isley, Ashford & Simpson. The investors were institutions, such as US insurance companies. One of Pullman’s companies, called Structured Asset Sales, LLC, is still active in the acquisition of copyright, but also in high profile IP infringement proceedings40Cf. the (rejected) copyright infringement case against Ed Sheeran, online: Structured Asset Sales LLC vs Sheeran et al, U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York, No. 20-04329. David Pullman revealed to us in an interview that he has not yet performed a transaction on French songs, but that he envisaged it, and that he is interested in the interpretations of certain French singers, without it being possible here to give more details.. However, there is no recent example of American securitisations implemented for a single author and performer.

Some particularly pugnacious SPVs initiating IP infringement proceedings are reminiscent of patent trolls or, more broadly, beyond patents, IP trolls41Lazarègue A., « Le phénomène du “copyright trolling” ou lorsque les agences de presse exercent des recours abusifs pour protéger leurs droits d’auteur », Le Monde du droit, 30 September 2021, online: https://www.lemondedudroit.fr/decryptages/77648-phenomene-copyright-trolling-agences-presse-exercent-recours-abusifs-proteger-droits-auteur.html.. These are companies that buy intellectual property rights, not to exploit them, but to threaten third parties to take IP infringement action against them if they do not pay them a (generally high) sum of money as compensation. However, investment or securitisation funds are not such structures, as they essentially have a financing purpose.

As of 1997, some rating agencies, such as Duff & Phelps42“DCR Comments on Music Royalty Securitizations” Special Report, Duff & Phelps Credit Rating Co., September 1999, online: https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~igiddy/cases/music.pdf. and especially Moody’s, intervened in this market by valuating the securities. While Moody’s seems to have moved away from the music rights securitisation rating market since the 2007-2008 crisis, KBRA is now actively offering this service.

In 1999, SESAC initiated pioneering securitisation in the field of rights management. This commercial company is entrusted by copyright holders to grant licences for the public performance of musical works. It used the securitisation of income from television and radio copyright exploitation for an amount of €29 million43“Moody’s rates SESAC Music Royalty Backed Music Deal”, 12 May 1999, online: https://www.moodys.com/research/MOODYS-RATES-SESAC-MUSIC-ROYALTY-BACKED-DEAL-Aaa–PR_28064..

In March 2001, Chrysalis Group PLC completed a £60m securitisation of the global catalogue of its music publishing rights44Horowitz R., “Securitisation: music to Chrysalis’ ears”, The Treasurer, May 2001, online: https://www.treasurers.org/ACTmedia/May01TTHorowitz49-51.pdf.. The transaction involved a loan being extended to Chrysalis Music Ltd in the UK by Music Finance Corporation, an ad hoc entity funded by a commercial paper. The securitised catalogue comprised 50,000 titles marketed in the UK, the US, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands.

With the subprime crisis, the securitisation of atypical assets, including music rights, seemed to wane almost completely.

However, since 2019, and especially in recent months, we have seen major transactions on catalogues of various songs. These transactions no longer focus on the titles of a single artist, but on a diverse catalogue of authors & performers.

Thus, in August 2019, SESAC Performing Rights, Inc. and some of its subsidiaries contributed a large number of their income-generating assets to companies issuing financial securities45KBRA Assigns Preliminary Ratings to SESAC Finance, LLC, Series 2019-1, 23 July 2019, online: https://www.kbra.com/publications/RwqgrWFh/kbra-assigns-preliminary-ratings-to-sesac-finance-llc-series-2019-1?format=file; Morningstar, SESAC Finance, LLC, Series 2019-1, 19 July 2019, online: https://ratingagency.morningstar.com. Investors subscribing to these titles were guaranteed payment of current and future music rights licenses.

The investment company Northleaf Capital Partners launched its first securitisation of music royalties in December 202146KBRA Assigns Preliminary Ratings to Crescendo Royalty Funding L.P., 14 December 2021, online: https://www.kbra.com/publications/gqhmhJKB/kbra-assigns-preliminary-ratings-to-crescendo-royalty-funding-lp?format=file.. The music rights catalogue was valued at $467.4 million. Only one notes class was issued by Crescendo Royalty Funding L.P., a Delaware-based company.

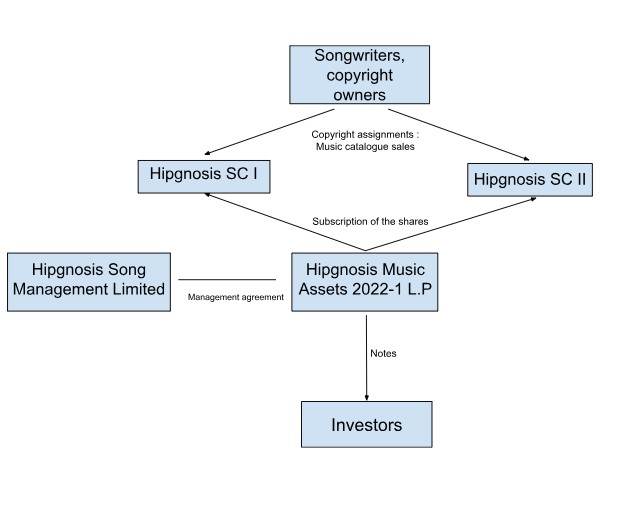

In 2022, Music Assets 2022-1 was introduced as the first music royalties securitisation of the Hipgnosis Songs Assets fund based in Delaware47KBRA Assigns Preliminary Ratings to Hipgnosis Music Assets 2022-1 L.P., 2 August 2022, online: https://www.kbra.com/publications/jRjPNHTc/kbra-assigns-preliminary-ratings-to-hipgnosis-music-assets-2022-1-l-p?format=file.. The arrangement used is rather complex: the US company Hipgnosis Music Assets 2022-1 L.P. subscribed to shares of two other US companies called Hipgnosis SC I and Hipgnosis SC II. The latter acquired copyright from rights holders, who were mainly famous US authors and performers. Hipgnosis Music Assets 2022-1 L.P. issued notes to investors. The amount of the dividends depends on the royalties of a music catalogue consisting of more than 950 songs by successful artists. The royalties include the publishing rights and the sound recording rights. The rate of securities issued to investors is 5% and is paid twice a year. An independent valuation company estimated this catalogue at $341 million using a discounted method for future flows and a discount rate of 7%. The catalogue is administered by several labels and publishers, including Sony Music Group, Universal Music Publishing Group and Warner Music Group. They are responsible for collecting licence fees on behalf of the copyright owner, and in return they take a commission for their services. The manager of this transaction is Hipgnosis Song Management Limited, a music investment company founded in mid-2018 by Merck Mercuriadis, the former manager of many renowned artists. To limit the risk of concentration, the songs in the catalogue are diversified according to artist, genre, age and source of income. The simplified diagram below indicates the main contracts and stakeholders. Schematically, payment flows circulate in several stages: the purchase prices of music catalogues are paid to copyright holders through the price of the financial securities subscribed by the investors; Hipgnosis SC I and Hipgnosis SC II receive royalties from multiple licensees; these royalties are paid in the form of dividends to Hipgnosis Music Assets 2022-1, which redistributes this money to investors in the form of interest and capital.

Simplified diagram of the arrangement

In June 2022, SESAC 2022-1 represented the second series of bonds issued by SESAC Finance LLC, following an issue of securities in August 201948KBRA Assigns Preliminary Ratings to SESAC Finance, LLC Series 2022-1 Senior Secured Notes, 27 June 2022, online: https://www.kbra.com/publications/HTqjYtXj/kbra-assigns-preliminary-ratings-to-sesac-finance-llc-series-2022-1-senior-secured-notes?format=file.. This transaction is presented as a whole business securitisation, insofar as a large number of assets were contributed to an ad hoc company. The underlyings include existing and future music affiliate agreements, current and future licensing agreements and intellectual property.

In February 2022, Hi-Fi Music IP Issuer II L.P. issued securities remunerated through music rights royalties49KBRA Assigns Preliminary Ratings to Hi-Fi Music IP Issuer II L.P., Series 2022-1, 3 February 2022, online: https://www.kbra.com/publications/vqmGbcsL/kbra-assigns-preliminary-ratings-to-hi-fi-music-ip-issuer-ii-l-p-series-2022-1?format=file.. This transaction is the first royalty securitisation by KKR Credit Advisors, a subsidiary of KKR & Co., which is a global investment company in the music industry. The catalogue belonged to Kobalt Capital Limited and was administered by Kobalt Music Publishing, a music publishing company. An independent valuation company valued the catalogue at $1.127 billion. Catalogue revenues include publishing royalties, sound recording royalties and recoveries of advances to artists. The rating report shows six pending IP infringement proceedings targeting songs that earn less than 1% of the securitised catalogue’s cash flow.

But even more recently, in November 2022, a rating report was published on a first issue of securities by Concord Music Royalties, LLC, an ad hoc company under US law50KBRA Assigns Preliminary Ratings to Concord Music Royalties, LLC, Series 2022-1,23 December 2022, online: https://www.kbra.com/publications/TkJrpBQP/kbra-assigns-ratings-to-concord-music-royalties-llc-series-2022-1?format=file.. This transaction was initiated by the US company Concord, which specialises in the acquisition, production and management of music catalogues and public representation rights of artists worldwide, covering several genres and vintages. Concord has a team of around 600 employees, with offices in the United States, Europe (London, Berlin), Australia and New Zealand. In these securitisations, the subscribers of these titles are paid thanks to the royalties of a music catalogue comprising more than a million songs by famous songwriters. The royalties come from both publishing and recording rights. A valuation company estimated this catalogue at $4.1 million using a discounted cash flow method.

In a recent methodology document published by KBRA, the rating agency states that it has conducted 38 ABS music royalty ratings on nine transactions since 2020, with issues totalling more than $4 billion; only four of these transactions were made public51KBRA Releases Researches, Music Royalty ABS: The Beat Goes On, 31 March 2023, online: https://www.kbra.com/publications/xHPSNjvk/kbra-releases-research-music-royalty-abs-the-beat-goes-on?format=file.. KBRA states that intellectual property companies and investment funds, such as the Hipgnosis Songs Fund and KKR, acquire the rights and finance the purchase of their catalogues by reselling the rights to securitisation funds. These securitisations valuated by KBRA generally include a combination of publishing copyright and sound recording rights. According to the “360°” strategy, the income sources are very diverse:

| Income source | Medium | Description | Example of payers |

| Mechanical rights | Physical | Record sale (CD, vinyl) | Fnac, Amazon |

| Download | Digital sale on platforms | iTunes, Amazon Music | |

| Streaming | Licences with on-demand music platforms | Spotify, Amazon Music | |

| Representation rights | FM | Licences for broadcasting on FM radios | NRJ |

| Internet (web radio) | Licences for broadcasting on web radios | Pandora | |

| Satellite | Licences for broadcasting via satellite | SiriusXM | |

| Public representation | Licences for broadcasting in public places | Restaurants, bars | |

| Synchronisation rights | Adverts | Licences for incorporating music into an advert | Publicis, Omnicom Group |

| Films, TV, etc. | Licences for incorporating music into an audiovisual entertainment work | Netflix, Disney |

Securitisations of music assets are formed thanks to a favourable economic context:

– the development of music streaming platforms, which contrasts with the drastic drop in concert revenues due to the pandemic. Licensing agreements with platforms offer relatively regular and therefore predictable income. This “platformisation” gives rise to new sources of income. Recently, “superfan” subscriptions have enabled users to enjoy exclusive benefits and access to their favourite artists, at an additional cost. However, new emerging challenges must be addressed before and after investments. One of these is the multiplication of fake streams, i.e. processes which allow users to artificially increase the number of plays or views to generate an income52J.-Ph. Thiellay, « Faux streams, vrai phénomène : le CNM, avec les professionnels pour lutter contre la fraude », 16 Jan. 2023, https://cnm.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Note-Jean-Philippe-Thiellay-Manipulation-des-ecoutes-en-ligne.pdf., which skew the financial valuation of music assets;

– the purchase of music rights catalogues at a very high price, sometimes directly from artists who, generally at the end of their career, manage to “recover” their rights thanks to a significant capital;

– growing apprehension among financial players in the music sector about music rights as assets and in particular as securitisable assets;

– a tendency for professionals to draw inspiration from pre-existing securitisation packages to propose a new transaction.

However, as with any investment, these transactions are not risk-free. For music rights securitisations, rating reports highlight IP infringement risks and market risks. It should be noted that while the Bowie Bonds were rated A353A3 corresponds to an “upper-medium grade” rating. when they were issued in 1997, this rating was downgraded by three notches in 2004 due to the development of unauthorised music file exchanges54Moody’s, “Moody’s downgrades, Jones/Tintoretto Music Royalty Securitization to Baa3”, 15 March 2004, online: https://www.moodys.com/research/MOODYS-DOWNGRADES-JONESTINTORETTO-MUSIC-ROYALTY-SECURITIZATION-TO-Baa3–PR_79896?lang=zh-cn&cy=chn.. The exploitation of intellectual property rights is particularly troubled by new technologies, which are often unexpected and disruptive.

The rating reports at our disposal do not specify the details of musical works whose rights are securitised. This information can certainly be found in the prospectuses provided to investors on a confidential basis. We are therefore unable to specify whether works by French authors are part of these securitised catalogues.

Could these securitisations be applied to music rights held by French creators and companies? We could envisage an assignment of economic rights to a securitisation organisation. However, French securitisation law is not adapted to this type of transaction, since the French securitisation organisation is not authorised to be an assignee of intellectual property rights. There are two solutions: either to use another legal fund form, such as a specialised financing vehicle (SFV), which can acquire any asset, under certain conditions, including on the ability to be valuated; or to use a more flexible foreign law, such as Luxembourg law on securitisation organisations55Cf: Quiquerez A., La titrisation des actifs intellectuels, Larcier, 2013, and Quiquerez A., « La titrisation de droits de propriété intellectuelle : actualité et innovations », Communication commerce électronique, no 1, January 2023, p. 5-10.. Nevertheless, the unwieldiness, complexity and expense of securitisation arrangements make them difficult to replicate for asset portfolios valued below €30 million. Therefore, securitisation is not very accessible in France and not very attractive compared to other more traditional financing techniques (bank lending, factoring for commercial receivables, etc.). Similarly, SESAC’s transactions seem difficult to transpose to French collective management companies. It is true that these French collective management bodies can collect “income from the exploitation of rights and any revenue or assets resulting from the investment of this income”56Art. L. 324-11 of the Intellectual Property Code., which allows them to conduct royalty investment strategies. But, as their name suggests, the role of management bodies is to carry out acts of management or administration of rights, not acts of disposal, which includes the assignment of rights that have been given to them. Moreover, the right of unilateral termination by the rights holder carries a significant economic risk57Art. L. 322-5 of the Intellectual Property Code..

Acquisitions by joint ventures

Joint ventures (JVs) are companies created by two or more companies that do not belong to the same group and that pool their resources to carry out a project together for a few years. They are prevalent in new information technologies, the pharmaceutical and automotive sector, and some are established in the music industry.

They have different objectives, which may be combined:

– technology-based JVs: companies join forces to develop an innovative product, for example by creating a research and development (R&D) centre;

– commercial JVs: companies join forces to launch a product on a new market, for example in a new area;

– industrial JVs: a production centre is set up to mass-produce products using local human resources.

These three types of joint venture can be found in the music industry.

In 2007, BMG Music Entertainment and Warner Music Group Corp. invested in a company operating in China that was developing technology to distribute music downloads and other content on mobile phones. The investment was made in Access China Media Solutions, established in early 2006 as a joint venture between Tokyo-based Access Co. and the Seattle-based digital media company Melodeo Inc.58“Two labels invest in China wireless firm” Los Angeles Times archives, 24 January 2007, online: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2007-jan-24-fi-chimusic24-story.html.

Access China Media aimed to distribute Melodeo’s technology to wireless operators and handset manufacturers in China and other Asian markets. In 2003, Sony Music and BMG created a JV called “Sony BMG Music Entertainment”, primarily to compete with Universal Music Group. This new entity brought together the music activities (recording of artists) of both groups, but excluded the music publishing activities (management of catalogue rights), physical distribution and industrial activity (pressing of CDs)59Madelaine N., « Sony Music et BMG vont fusionner pour créer le numéro deux mondial de la musique », Les Échos 7 November 2003, online: https://www.lesechos.fr/2003/11/sony-music-et-bmg-vont-fusionner-pour-creer-le-numero-deux-mondial-de-la-musique-677032.. In 2004, Sony and BMG created a SPV in India called Swar Mala Entertainment India as a joint venture to produce and distribute CDs in Asia60Singh G., “Sony, BMG set up SPV for distribution”, The Economic Times, 21 August 2004, online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/brand-equity/entertainment/sony-bmg-set-up-spv-for-distribution/articleshow/822310.cms?from=mdr..

These are just examples, since joint venture operations are generally confidential, at least in terms of their details.

Joint ventures are relevant to the topic of financialisation in two ways:

– under a rationale of “strength in numbers”, independent companies can maximise their resources to facilitate access to cutting-edge technologies, financial markets and fairly cumbersome, complex and costly legal arrangements. However, from a legal point of view, it is necessary to be able to determine with precision and accuracy the holders of the rights to music titles. Music rights can be transferred by assignment or company contribution. The JV will not necessarily acquire the music rights, but simply take charge of operational management and activity.

– these JVs can be financed by issuing financial securities to various investors, including investment funds, to meet needs covering ambitious projects.

In France, there are no legal obstacles to the creation of joint ventures in the music industry. Some have already been established in France, particularly to organise music festivals61For example, a JV named OL Productions was created in the form of a simplified joint stock company (SAS) with the aim of organising and managing an annual music festival. The capital of this structure was divided equally between OL Groupe and Olympia Production..

Indirect investments in music assets

Indirect investments can be made through the acquisition of shares (2.2.1), royalties (2.2.2) or, more recently and innovatively, through tokenisation (2.2.3).

The acquisition of shares by banks and investment funds

An alternative way for banks and investment funds to intervene in the music market is to become partners of music publishing companies. In other words, these banks or funds buy back the shares of music publishers from their current partners. They then become majority or minority partners depending on the amount of their acquisition. This is a private equity approach applied to the music industry. Such transactions are mainly conducted in the United States and the United Kingdom.

A notable transaction was conducted in 2021 by the New York-based investment company KKR & Co. Inc. and the family office Dundee Partners LLP for $1.1 billion from KMR Music Royalties II’s portfolio. This Luxembourg fund held music publishing rights to over 62,000 titles.

Another major fund, Blackstone Inc., purchased the Canadian music company Entertainment One, an entity of Hasbro Inc., for $385 million62Tezuka M., Wilson D., “PE targets digital music rights; US, Europe PE deals rise”, S&P Global Market Intelligence, 29 October 2021, online: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/pe-targets-digital-music-rights-us-europe-pe-deals-rise-67326138..

In 2001, the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec created CDP Capital Entertainment, a Los Angeles-based company with the mission of seeking out investment opportunities in the entertainment sector and offering consulting services to businesses in this sector. The new company managed a CAD 300 million portfolio, including investments in three industry leaders: MGM, Mosaic Media Group and Signpost. It invested CAD 32 million in Mosaic Music Publishing63Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, 35e rapport d’activités, 2001, online: https://www.cdpq.com/sites/default/files/medias/pdf/fr/ra/ra2001_rapport_activites_fr.pdf..

Private equity firm Apax Partners bought Stage Three Music, a music publisher, for over £40 million in 2004, and a year later Stage Three Music acquired Mosaic Music Publishing64Davies M., “KKR-Bertelsmann venture buys Stage Three Music”, Reuters, 15 July 2010, online: https://www.reuters.com/article/kkr-bmg-idUSN1417045220100715.. In 2010, Apax Partners sold its shares to BMG.

The three US Shamrock Capital Content Funds (I, II and III), created since 2016, have a diversified investment strategy targeting the capital of companies that hold music, television and film rights, rights to broadcast sports events and rights to video games.

Could French banks invest in the capital of publishing or music production companies? From a legal point of view, French credit institutions may acquire and hold stakes in companies under the conditions laid down by regulatory texts65Art. L. 511-2 of the French Financial and Monetary Code.. In this context, Crédit Agricole bought 30% of Skyrock’s shares, before reselling them in 2021. However, the intervention of banks in the music sector currently tends to be deployed through patronage or sponsorship. The dynamic is different from that of French cinema, where the legal framework allows banks to create financing companies for the film and audiovisual industry (SOFICA). These are investment companies dedicated to raising private funds exclusively for film and audiovisual production. There is no similar financing company in France for music production.

The acquisition of royalty receivables

Some financing and investment transactions are not based on an assignment of copyright to a SPV. Instead, they are less cumbersome transactions which involve assigning royalty receivables to an operational company This type of transaction is very similar to factoring, in that it involves acquiring receivables that are not yet due. The acquired receivables are the right to payment of a sum of money, in this case derived from the exploitation of literary and artistic property rights.

For example, the US company Royalty Exchange offers three types of services for authors of musical works:

– an assignment of receivables arising from literary and artistic property rights;

– a total or partial assignment, for current works, of the copyright catalogue. The copyright owner retains the rights over future works;

– the creation of a royalty-backed NFT. The intellectual property title is registered on the blockchain. By purchasing an NFT, investors acquire some of the copyright, according to the contractual stipulations, and the author receives royalties.

This company presents its services as follows: “Royalty Exchange gives both retail and institutional investors access to royalty streams previously available only to industry insiders, private equity, or institutional funds. Through our unique marketplace, you can now build a portfolio of uncorrelated, yield-generating royalties with a documented track record of consistent income across multiple assets, price levels, and terms”.

As another example, ANote Music finances creators by assigning future receivables on their royalties. More innovatively, ANote Music operates as a music royalty exchange. The author’s music catalogue is put online and its auction price is established on the basis of income from the past three to five years. Investors then collect the catalogue’s operating income instead of the artist. The interest of the mechanism lies in its ability to divide the ownership of the catalogue into various shares and maturities.

The US start-up JKBX appears to be setting up a similar transaction. The aim of the project is to allow retail investors and music enthusiasts to invest in music royalties through an online platform.

The purchase of receivables is much more legally neutral, easier to set up and has less impact than the purchase of copyright. This type of transaction does not correspond to the acquisition of a music rights catalogue. As such, there is no change in ownership of the intellectual property rights, but simply a new creditor. It is based on the well-known civil law transaction of assignment of receivables. Sacem makes available to its members (creators, heirs, publishers) a receivables assignment model allowing it to pay to its members’ creditors the rights due to said members for the exploitation of their works, in accordance with the amount or percentage stipulated in the contract.

Utopia Music is a Swiss company that offers an accelerated royalties service, accessible to authors, producers and labels that earn at least €5,000 in royalties from the sale of their music or streaming. This financing technique is original because it does not seem to be based on an assignment of royalties, but on an advance of up to two years of royalties. Utopia Music’s client obtains and retains ownership of the intellectual property rights.

Tokenisation of music rights

Tokenisation is used for various transactions. The process refers to the issue – by means of a blockchain system (a distributed ledger technology, according to the legal definition) – of asset-backed tokens, in particular to facilitate the sale of all or part of the asset in question. There are various forms of tokenisation, such as (i) property tokenisation, (ii) initial coin offerings and (iii) the issue of security tokens, i.e. financial securities issued with digital tokens. The tokens issued can be fungible (interchangeable) or non-fungible (NFTs for non-fungible tokens).

Some US platforms, such as Band Royalty, allow artists to split and sell their music as NFTs. These NFTs give their owners a right to a share of the income generated by the song, especially via streaming.

360X Music AG has issued security tokens for music royalties in association with the German music rights management company GEMA. The tokens on the blockchain are intended for royalties relating to compositions by the German film music composer, Hans Günter Wagener. 360X music AG is a digital asset start-up supported by Commerzbank and Deutsche Börse. It provides a market regulated by BaFin for music, art and property66Spangenberg E., « La tokenisation de la propriété intellectuelle », La Semaine Juridique Entreprise et Affaires, no. 2, 13 January 2022.. These tokens are subject to German financial securities legislation.

In France, Bolero Music SAS offers the acquisition of “Song Shares”, which entitle buyers to receive a share of the operating income of the backed songs. These digital tokens have a market value and are transferable or exchangeable on a marketplace.

Specific features of the French catalogue acquisition market

Catalogue acquisitions are subject to administrative, legal and financial constraints. These different aspects each respond to specific situations that help to optimise the acquisition of music assets. Music assets have many specific characterises and the situations differ from one territory to another, with France being no exception. The key indicators need to be handled with caution in response to a specific market in some respects. These specific features are observed through the acquisition multiples (3.1) and the difficulties of entering the French market and exporting French songs (3.2). The French catalogue acquisition market thus remains controlled by traditional players (3.3). However, a new dynamic is emerging (3.4).

Acquisition multiples, the pulse of the market

A study drafted by Henderson Cole, Kaitlyn Davies and David Turner67Cole H., Davies K. and Turner D., Deux décennies d’achats de catalogues musicaux, op. cit. informed readers about the number of acquisitions as well as the financial volumes engaged over the past 20 years and demonstrated the dazzling development in acquisitions since 2018. We felt that it would be interesting to try to complement these last indicators with the evolution of the multiple acquisitions68The acquisition multiples indicator reflects the amounts that market players are prepared to invest. The higher the average multiples, the higher the expected future income of the catalogues; the former thus give an important indicator of market confidence. conducted in the field of music publishing. When it comes to acquisition multiples, we prefer to look at the net publisher’s share (NPS), i.e. the net amount of royalties collected by the publisher, instead of the classic EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation), deducting those to be allocated to the rights holders (authors and composers), without including a publisher’s operating costs. Globally, these indicators have doubled over the past decade, reaching a coefficient of 20 by 201969J.P. Morgan Cazenove, Goldman Sachs, Barclays Research, Guggenheim, RBC Capital Markets, Evercore ISI, SunTrust (Truist Securities), Morgan Stanley, Shot Tower.. Fast-paced communication in the UK and the US has caused a frenzy that is already reflected in markets and future projections, with average multiplier coefficients expected to be around 15 in the coming years.

These staggering indicators, which can illustrate the latent aggressiveness of the international market, are unfortunately often taken as standards by some French rights holders in the expectation of a future sale. Music assets related to French songs have much less potential for exploitation due to two main factors:

– reduced territorial exploitation: French works whose notoriety is confined to certain territories benefit from a smaller audience base than major international successes;

– much fewer opportunities for covers or synchronisations: as the notoriety of works stops at certain borders, this reduces the potential secondary exploitation in third territories. The digital share, and in particular the growth of streaming, in the income of works, is a key parameter in this regard, considering the maturity of the different markets.

A French assets market that is hard to penetrate and assets that are difficult to export

An acquisition is not simply the enjoyment of an asset, it is also the strengthening of its exploitation together with contractual and commercial obligations. French assets are very particular in this respect. The French market, which is structurally different from that of the United States, commonly includes in publishing contracts an assignment of rights “à vie”, i.e. for 70 years after the author’s death. The rights thus held by publishers can only be recovered by the songwriter after a given exploitation period and under certain conditions. This factor eliminates a large number of opportunities on the French market70It should be noted that the French publishing market is changing, opening up different possibilities: certain contracts which do not feature this lifetime retention, the integration of termination clauses or adjustments under different conditions.. The assets sold are limited to catalogues of “professional” publishers or authors and composers who have chosen to retain their publishing rights during their career.

The exploitation of French assets is also distinct from British and American assets. Exploitation opportunities and prospects are reduced by certain factors:

– in the months following the acquisition of a catalogue, we can observe an almost systematic increase in its income, ranging from 5% to 10%. This increase comes from an update and an administrative enrichment of the catalogues on an international scale. In France, the income from these catalogues prior to the acquisition is already optimised; there is therefore no prospect of increasing the post-acquisition value. French songs are indeed less exposed to the risk of dilution in an abundant international offering and enjoy Sacem’s remarkable collection efficiency on French territory;

– the development of emerging markets and their growth make it possible to expect future income from international assets. The prospects for the exploitation of French assets in the Chinese or Indian markets, for example, seem less certain, although not impossible;

– opportunities for new exploitation (synchronisation or cover) of a French work are also diminishing.

But this territorial specificity also creates a barrier to entry into the French market. Local exploitation requires certain knowledge; expertise of the French market is needed to guarantee the exploitation of a local catalogue. Moreover, as all business practices are conducted in French, it is more complicated to carry out negotiations in English in France.

These specific features and various contractual, administrative and commercial obligations make the French market difficult to approach for a foreign player. One prerequisite for such an acquisition would be, at the very least, for the new player to become established in France.

However, an internal market has existed in France for many years.

An acquisition market controlled by “pure players”

With their confidential and discreet approach, French players and their acquisitions are far removed from the ardent communication emanating from American and British operators. Our study does not seek to be tinged with sensationalism, but simply to offer a global overview of the market and explain some of the reasons for its current state and the consequences of an international dynamic. Many catalogues, or parts of catalogues, have changed ownership in recent years. Some directly involved specific songwriters, such as Gilbert Bécaud, Alain Souchon, Jean-Jacques Goldman, Michel Polnareff, Alain Chamfort, Gérald de Palmas, Louis Chedid, or Michel Jonasz in recent weeks, to name but a few; others involved more or less extensive publishing catalogues: Éditions Musicales Alpha, Éditions des Alouettes, Éditions Francis Dreyfus, etc.